Towards An Architectural Journalism

May 18, 2016 / 0 Comments

Alfredo Cramerotti’s book Aesthetic Journalism: How to Inform without Informing (2007) explores the relationship between contemporary art and documentary journalism, challenging established definitions of each. This blurring of the margins between art and journalism Cramerotti terms Aesthetic Journalism, a strain of contemporary art in which artists using the tools and methodologies of investigative journalism — archival and field research, interviewing, documentary and narrative storytelling, surveys, infographics and other display formats — offer alternative views of reality, political and otherwise, than those presented by mainstream media. The result of the artist’s research operates within an artistic context not the channels of the news media, although it is used as a critical instrument of investigation for a whole host of social, cultural and political situations that challenge notions of journalistic truth and objectivity.

As a critic originally trained in the Woodward-Bernstein school of investigative journalism and who came to the field of art criticism in the mid-1980s via my aborted aspirations to become a political reporter, Cramerotti’s text has been deeply influential to my search for new critical models. If the field of art has become the new laboratory for journalistic experimentation, what can we as journalists take from the world of art? What constitutes a creative critical practice? What forms might an “artistic turn” in criticism take?

In an attempt to answer these questions, it is helpful to look at some of these artistic models. Cramerotti traces some of the roots of Aesthetic Journalism to certain conceptual art practices of the 1960s, citing works by Martha Rosler and Hans Haacke, while noting the importance of Documenta X (1997), one of the first large-scale representations of this hybrid practice. Some of the contemporary artists and projects he notes include Alfredo Jaar, the Atlas Group, the collaborative Multiplicity, Renee Green, Lucas Einsele and several others who employ information systems to explore political subjects. To this sample I would add the artists: Hito Steyrel, whose videos combine new documentary forms and highly subjective narratives to critique the ways in which images are controlled and disseminated; Yael Bartana, whose films and videos pastiche traditional documentary techniques and socialist-realist propaganda to speak to issues of nationalism; Irina Botea, whose videos employ role-playing and re-enactment techniques to remediate moments of historical trauma; Trevor Paglen, whose photographic practice unmasks covert government information systems and makes visible the politics of surveillance.

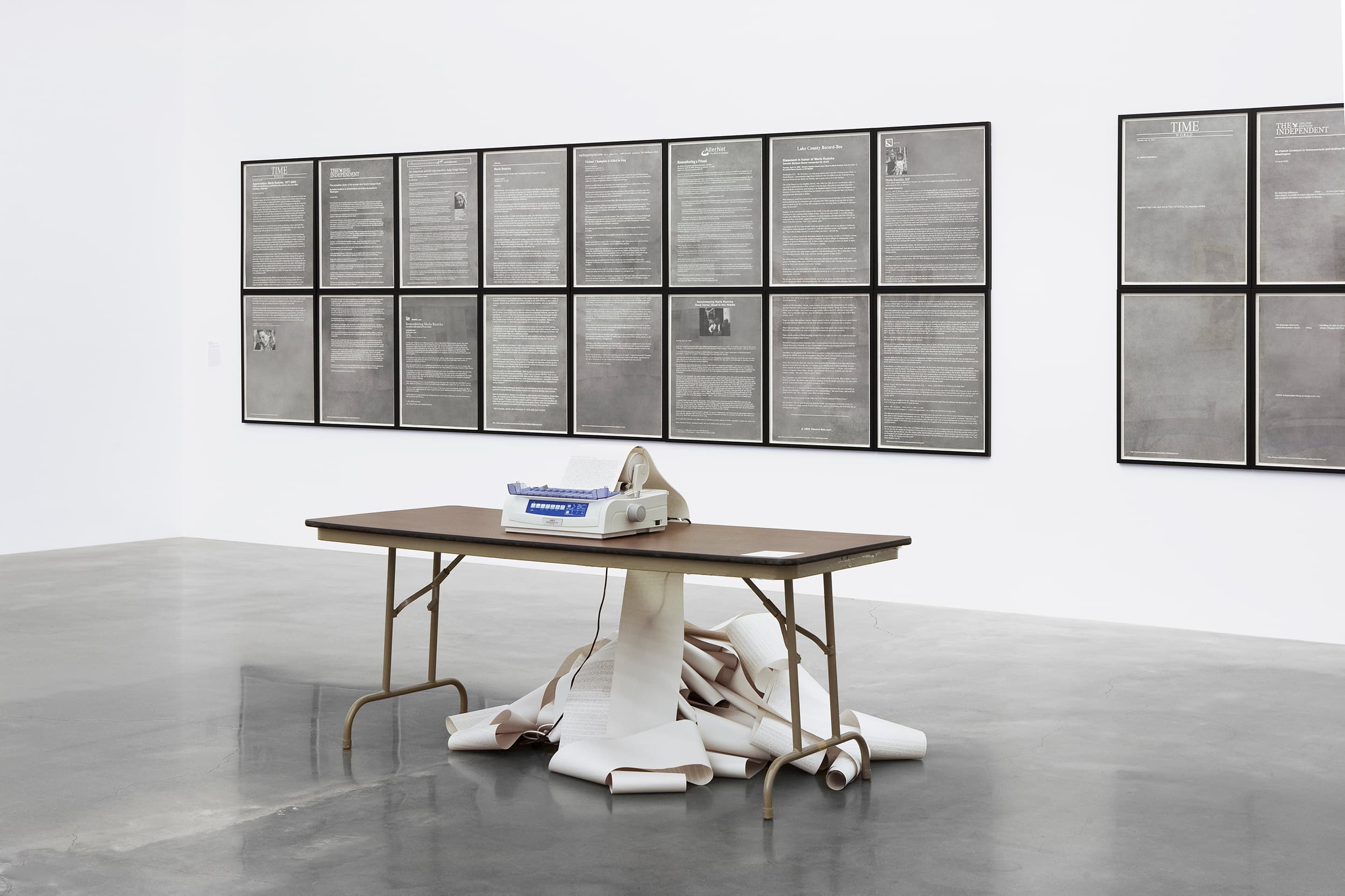

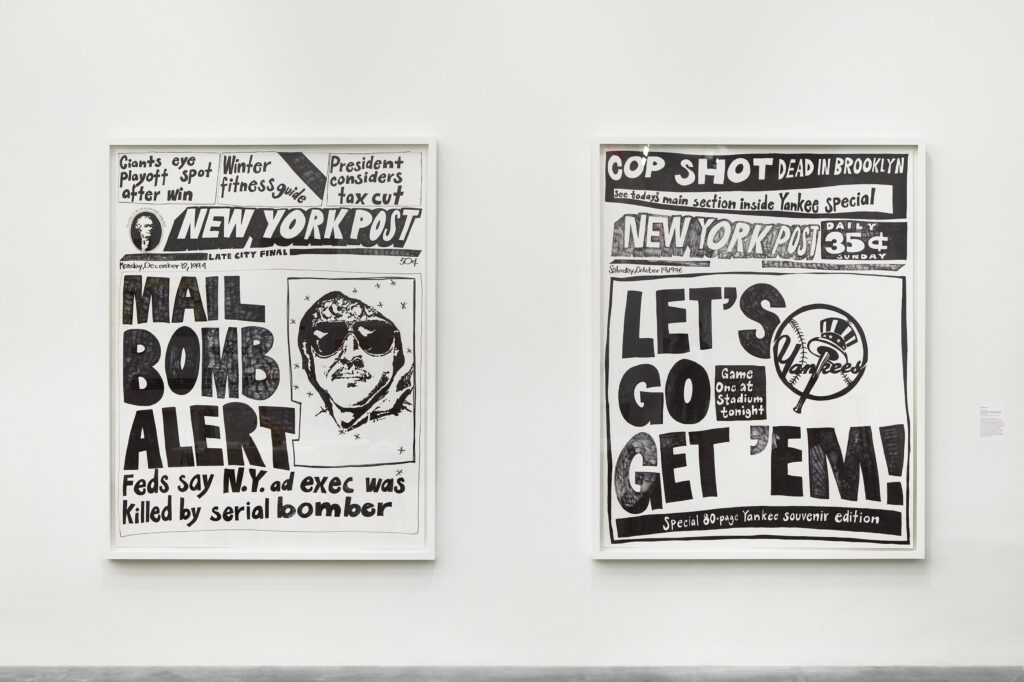

This shared trajectory of art and journalism has operated within a number of gallery and museum exhibitions as well. One such key example is the exhibition “The Last Newspaper” (on view at the New Museum, New York, in 2010), a group show surveying how various artists approach the news. Included, for instance, were a recreation of William Pope.L’s performance Eating the Wall Street Journal; a redo of Hans Haacke’s The News, a live feed of the daily news via a TELEX machine; Alexandra Mir’s oversized drawings of the front pages of The New York Post; and Angel Naverez and Valerie Tevene’s video interview of The New York Times obit editor, entitled A Dutiful Scrivener.

In addition to individual artworks were a number of partner organizations (ex. StoryCorps) and artist collectives, who facilitated public dialogues and interactive information sharing sessions, and staged on-site micro-newsrooms that reported on and responded to the artworks and ideas within the exhibition. The Barcelona-based Latitudes produced a weekly newspaper that documented the show during its ten-month run in lieu of an exhibition catalog, soliciting viewers to pitch editorial content. Issues of The New City Reader, a large format tabloid produced by Joseph Grima and Kazys Varnelis, were postered in public places throughout the city.

I am interested in these kinds of embedded or “pop-up” media environments as potential models for reimagining the 21st-century newsroom and for offering architectural structures/infrastructures that are site responsive, adaptable, permeable. An “Architectural Journalism,” if you will, then, offers a physical space for various forms of on-site publishing, as well as a discursive space that activates the production of critical dialogue with multiple participants that is immediate and in direct conversation with the works on view.

One sees connections between these spaces and various alternative media practices of the 1970s, some of which are explored in the current traveling exhibition “Hippie Modernism: The Struggle for Utopia,” an examination of global architectural and design practices of the 1960s and ‘70s organized by the Walker Art Center. Here, DIY architecture, experiential media environments and independent publishing projects (ex. The Whole Earth Catalog) capture the utopic spirit of the hippie movement and the emergent technologies that shaped today’s online world, while offering an alternative vision of modernism.

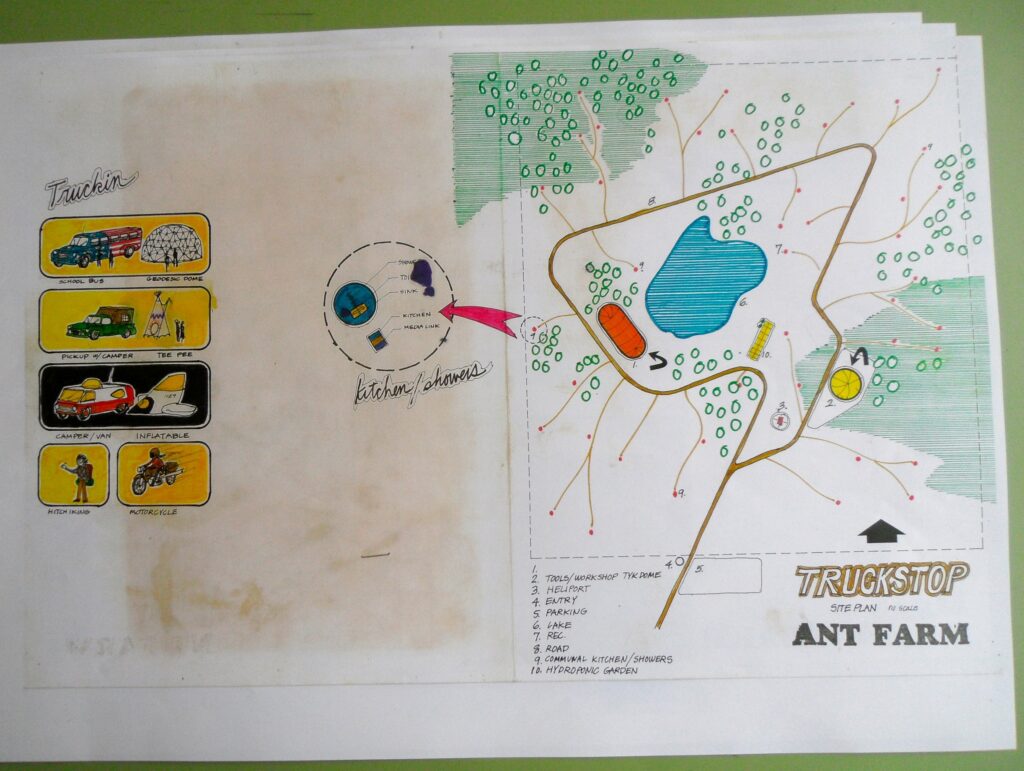

Projects by the San-Francisco collaborative Ant Farm and architect Ken Isaacs are important to my argument here. Ant Farm’s Truckstop Network (1971), a multi-tiered project in which this collective of architects working alongside media artists proposed a series of information exchanges using trucks and vans outfitted with media equipment. Part road trip, part roadside pedagogy, the goal, as envisioned through drawings, texts, videos and other documentary materials, was to create a mobile architecture that would traverse the United States to document encounters with the American public and to create an alternative network for the exchange of ideas.

Isaacs’ Knowledge Box (1962/2009), an experimental learning chamber for which I served as a curatorial advisor, eschews the traditional classroom for “environmental concepts of education.” Upon entering the darkened chamber, the viewer is suddenly immersed in a rapid montage of sounds and images via a slide program or “magazine” of vintage black-and-white photographs culled from Life magazine. This experimental environment brings about a social awareness that allows the viewer to bring his or her own experience to the learning process. The ultimate goal: a transformation of consciousness.

Writing about his “alpha chambers” in 1967:

“It was necessary to develop a situational, experiential tool which could break the culture grip and provide purchase to the new data assemblies which were being ignored and excluded from the current worldview. The communications environment had to be shocking, evocative and total. Culture itself is such a pervasive ubiquity that nothing less than a total tool could deal with it. The only communication situation would be one which offered the probability of deep and total involvement for the participant.” (Note 1).

The Knowledge Box was originally created in 1962 in collaboration with students at the Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago, where Isaacs taught, and recast in 2009. Its design is based on Isaacs’s idea of the matrix, a three-dimensional grid that forms the central concept and building component of all his work, including his popular Living Structures. These total living units were often referred to as information structures, given the architect’s integration of what he termed “pholages,” scrims or panels of photographs collaged from popular magazines in which the viewer creates meaning through the juxtaposition of images.

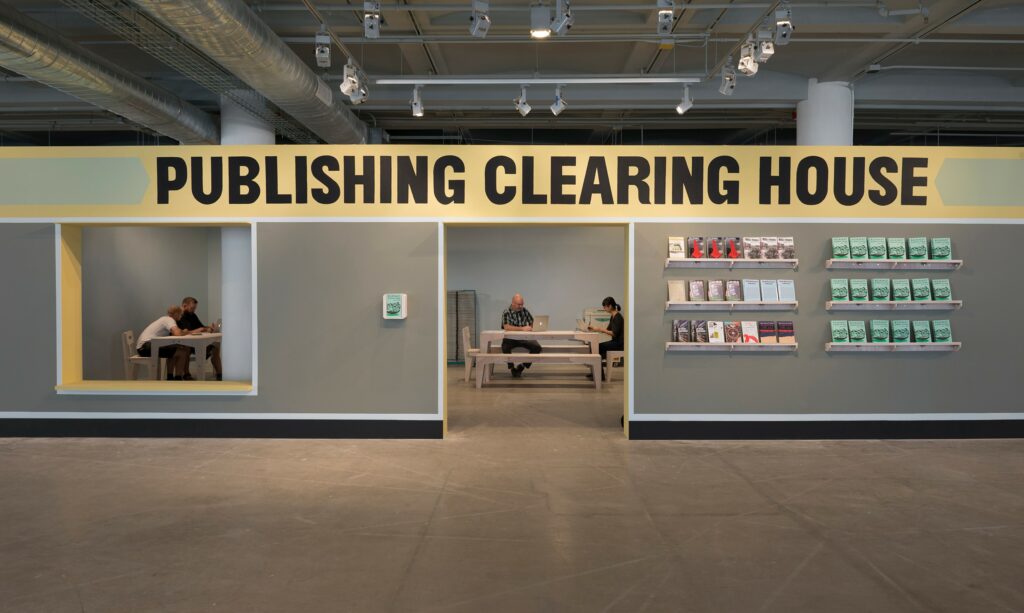

More contemporary examples of participatory critical practices, or what I am now terming Architectural Journalism — again a journalism that is both dialogical and spatial – are found in several experimental, independent publishing projects, mainly spearheaded by artists. Self-publishing is central to the practice of the Chicago-based collaborative Temporary Services (Marc Fisher and Brett Bloom), whose public projects often include books, posters, newspapers, and other forms of printed matter, published under the auspices of their publishing imprint Half-Letter Press. For Publishing Clearing House, a temporary print shop created for and sited within the group exhibition “A Proximity of Consciousness: Art and Social Action” (on view at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in fall 2014), Temporary Services invited collaborators (artists, writers, youth groups) to develop and produce new publications “in-situ” during the exhibition.

Elsewhere, this artist collaborative has created installations within exhibitions where self-published books are suspended eye level from the ceiling in clusters or “book clouds” to offer an open and shared space for collective reading. For Temporary Services, books and publications are inherently social, from their material inception to the economies of labor involved in production to the experience of the reader. “Printed materials actively inhabit our spaces and exist as social entities,” the artists have stated. “[T]hey are a social-spatial currency.” (Note 2)

Other publishing projects such as Green Lantern Press in Chicago and Publication Studio in Portland, Oregon, share similar interests in the social and, in particular, community function of publishing artists books through their multi-disciplinary programs that combine publications with exhibitions, residencies and public events that foster conversation. Publication Studio co-founder Matthew Stadler describes publications as “the creation of a public.” “The public is created through deliberate, willful acts: the circulation of texts, discussions and gatherings in physical space, and the maintenance of a related digital commons,” says Stadler. “These construct a common space of conversation, a public space, which beckons a public into being. This is publication in its fullest sense.” (Note 3)

A more interventional model of art publishing that directly engages broad publics in public spaces is the artist-run newsstand, in which artists install newspaper kiosks on city streets and in subways for the distribution of independently produced artists books, periodicals and zines. Recent projects in New York (ALLDAYEVERYDAY and Petrella’s Imports), Toronto (The Artists Newsstand), and San Francisco (The Grand Newsstand) suggest a growing trend, although many appear to be rather temporal. I see affinities here between the artist newsstand and the information kiosks envisioned by Rodchenko and other Russian Constructivist artists, as well as Bauhaus architect Herbert Bayer’s 1924 design for a newspaper stand. The function of Rodchenko’s kiosk, while highly influential but never realized, was the dissemination of publicity and information for the Soviet state. This was to be achieved through the integration of multiple information systems into one architectural structure: “a large clock, a huge billboard positioned above the building, a speaker’s rostrum, a screen for advertisements, a place for posters, and a space for the sale of books and newspapers.” (Note 4)

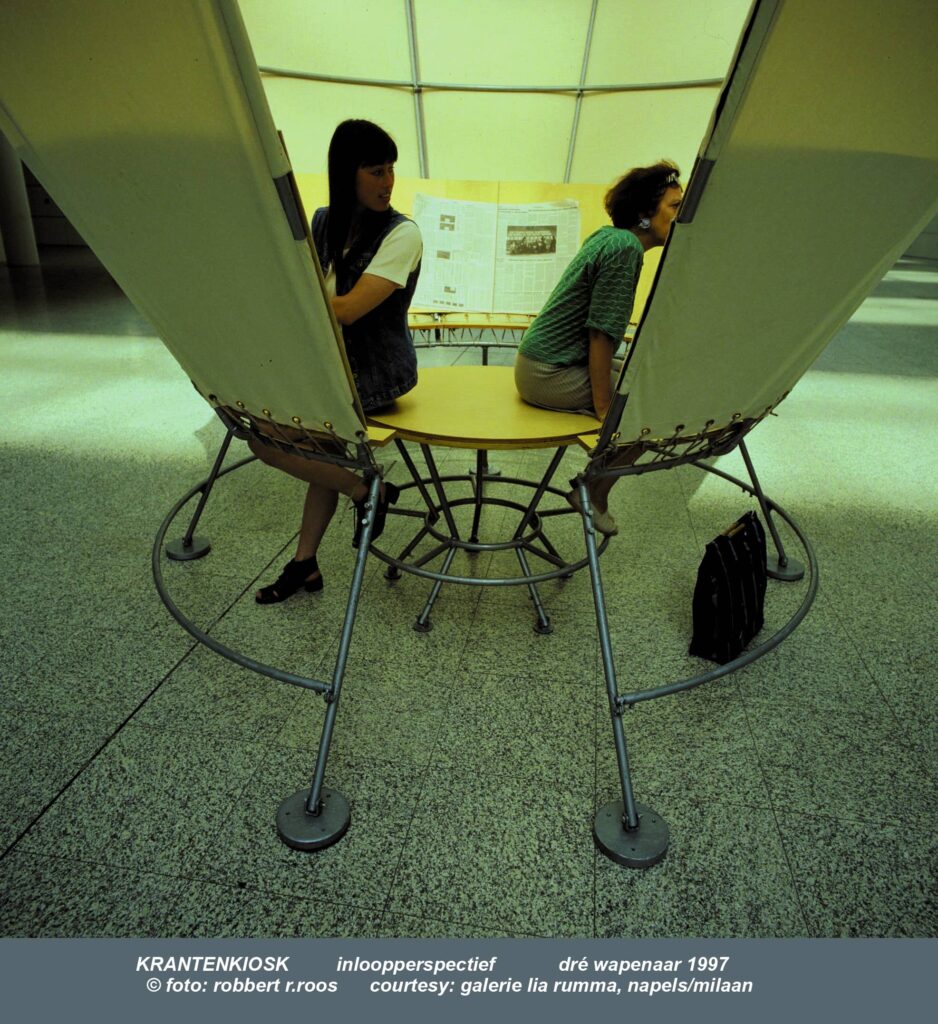

The community function of a Newspaper Kiosk (1999) designed by the Rotterdam-based architectural studio of Dré Wapenaar resides in its ability to adapt to various public sites and in the creation of an intimate space for social rather than economic exchange. Known for his tentlike structures, Wapenaaar’s Newspaper Kiosk is similarly constructed from a tensile canvas stretched over a steel armature, the interior of which houses wood seats and shelving.

According to Fieke Konijn:

“The Newspaper Kiosk has been deployed in the Rotterdam public library and in the atrium of The Hague’s city hall. It is precisely in such surroundings in which the piece comes into its own, standing like a communications satellite returned to earth from space, an airy defence against the surrounding hustle and bustle. Readers sit with their backs to each other on a circular wooden platform in the middle of the tent. This attitude allows them to immerse themselves in the newspapers placed on the counter in the outer circle. Passers-by only see their legs, which they can rest on a circular bar. In this tent, Wapenaar has opted for movement from the centre outwards, which strikes me as a good metaphor for communication. The reading does take place in temporary isolation, but the shared seat can nonetheless make it an occasion for contact between readers.”(Note 5)

While these examples might be viewed as more critical artistic practices versus artistic critical practices, the participatory and social dynamics of these publication projects is what interests me and what I am hoping to recuperate for art criticism. Combined with the experiential encounters offered by the various media environments discussed here, criticism might also be a physical and spatial practice. This might manifest in more micro- and pop-up newsrooms sited within exhibition spaces, community centers, libraries, schools, or public parks; or publication residencies. More roaming mobile media units that allow easy public access and idea sharing across social media and other wide-ranging technologies. The reinvention of the newspaper kiosk as a social hub for the distribution of art publication and critical exchange. In the end, Architectural Journalism is criticism in its most public sense.

Notes

- Ken Isaacs, “Alpha Chambers,” in Dot Zero, no. 4, 1967, p. 40.See also, my interview with Isaacs: http://www.walkerart.org/magazine/2015/enter-matrix-interview-ken-isaacs.

- Temporary Services, Publishing in the Realm of Plant Fibers and Electrons, 2014, pp. 8-9.

- See http://www.liquisearch.com/matthew_stadler/publishing_and_public_space. Accessesed May 18, 2016.

- Victor Margolin, “Visions of the Future: Rodchenko and Lissitzky, 1917-1921,” The Struggle for Utopia (University of Chicago Press, 1997), p. 17.

- See http://www.drewapenaar.nl/project.php?id=85&text=.