The Chicago Architecture Biennial 2.0: Axes and Praxes

October 17, 2016 / 0 Comments

The recent announcement of the new artistic team to lead the 2017 Chicago Architecture Biennial (CAB) has prompted me to consider some of the political dynamics at play and to share a few ideas about what I think the next installment of CAB could be. Sharon Johnston and Mark Lee of the Los Angeles-based firm Johnston Marklee are its Artistic Directors, following 2015’s Sarah Herda and Joseph Grima, with Todd Palmer, of Chicago’s National Public Housing Museum, as Executive Director.

Johnston Marklee brings an insider’s perspective to the project both as a participant in the inaugural biennial and as practicing architects. Their clean, minimalist designs favor bold geometry (polyhedrons, stacked or interlocking rectangular planes, dramatic curved volumes) and the integration of public and private spaces, an aesthetic they have brought to several high-profile residential houses and to various art-related commissions, among them a new campus for the UCLA Graduate Art Studios in Culver City, California, the Grand Traiano Art Complex in Grottaferrata, Italy, and the Menil Drawing Institute, Houston, Texas, opening next year. The architects often collaborate with designers and artists (for example, Luisa Lambri, Marianne Mueller, Jack Pierson, James Welling) in their initial research, an interdisciplinary process revealed in a series of photo collages that render their housing projects as abstract forms and on view at the Chicago Cultural Center during the first edition of CAB.

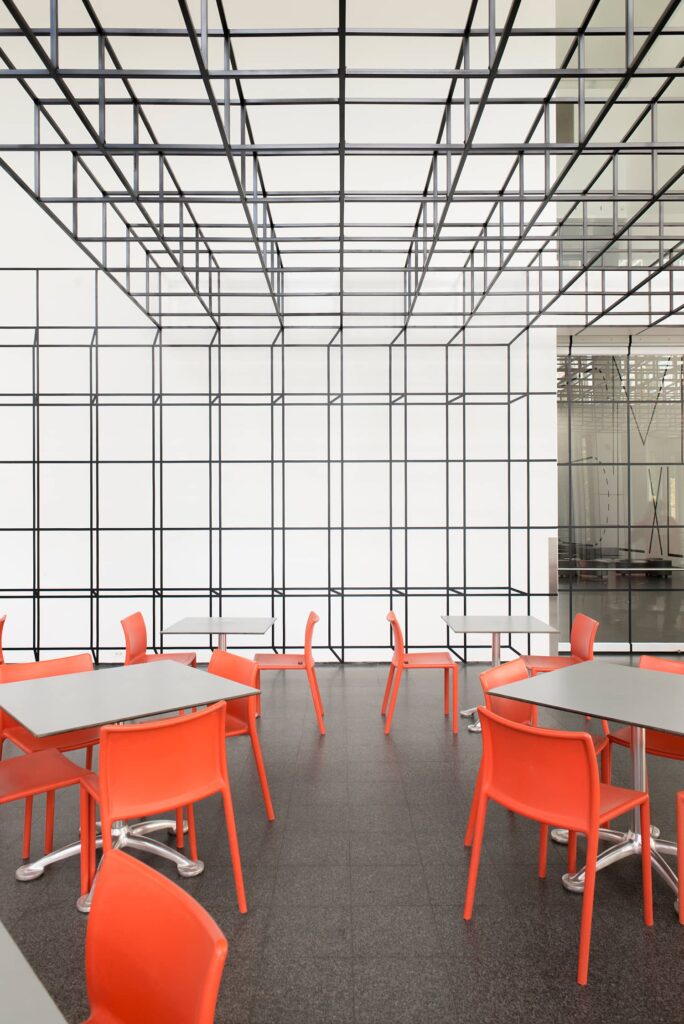

Johnston and Lee’s connection to Chicago extends beyond their new roles as the biennial’s Artistic Directors. Their firm is leading the redesign of the Museum of Contemporary Art’s (MCA) interior spaces, which includes the creation of an “engagement zone” for public events and education programs, and the relocation of the restaurant to street level. Their intervention in the current MCA café A Grid is a Grid is a Grid is a Grid is a Grid, an aluminum gridded ceiling structure and wall graphic, references the “poetic rationalism” of architect Josef Paul Kleihues’ original building, and also hints at their proposed design.

Johnston Marklee was also chosen as the architecture firm for the proposed Green Line Arts Center, part of The Arts Block development, a 100,000-square foot stretch of East Garfield Boulevard to be converted into an arts corridor. The Arts Block is a project of the University of Chicago and will be led by artist Theaster Gates, whose Stony Island Arts Bank opened under the auspices of last year’s biennial and whose close relationship with Mayor Rahm Emanuel, the driving force behind CAB, is well known. While building on existing relationships isn’t necessarily a bad thing, one might ask, under what process and criteria is CAB leadership chosen?

Johnston Marklee’s vision for CAB offers, perhaps, some insights, and is based on the following themes: the axis between history and modernity, and the axis between architecture and art. To this first axis, their vision calls for a “rediscovering of [architecture’s] own roots and traditions,” in response to the field’s fascination with the new and the “latest micro-trends.” As declared in their press statement: “The insistence on being unprecedented and unrelated to architectures of the past reached new heights at the beginning of the millennium, as more and more architects became reluctant to consider what they do as being part of a larger collective project or part of a longer architectural history.” (Note 1) However, definitions of modernity are never clearly articulated nor are the architectural histories to be reconsidered. My hope is that the well-known platitudes of Western modernism and its architectural icons, such as the many that occupy the Chicago skyline, are not the only histories to be examined. Likewise, their claim for an architecture that “celebrates shared values” seem at odds with what we now know of the modernist project. Post-modernism and global art and architectural histories have argued the importance of local political conditions on local production and given us a more horizontal view of cultural history, one that stresses plurality and difference rather than commonalities.

Svetlayna Boym’s idea of the “off-modern” might be a useful, alternative frame to consider architectural history:

“‘Off-modern’ is a detour into the unexplored potentials of the modern project. It recovers unforeseen pasts and ventures into the side-alleys of modern history at the margins of error of major philosophical, economic and technological narratives of modernization and progress.” (Note 2)

The second axis to be explored – the juncture between architecture and art – seems to take a more multidisciplinary view, with Johnston Marklee noting the evolution of both practices in relation to public space, site-specificity, and changing national and civic identities. As I have written elsewhere in this blog, such collaborations have the potential for re-inventing the urban landscape, both as a physical and social space, for creating new points of public access and opportunities for community engagement, and for offering creative problem-solving to the many social challenges cities face.

With this in mind, I was somewhat skeptical when it was publicized that the opening of CAB 2017 (September 16- December 31, 2017) would coincide with next year’s EXPO Chicago (September 13-17, 2017), the annual fair of contemporary and modern art. EXPO Chicago then announced its partnership with the Palais de Tokyo in Paris for an artist residency program at Mana Contemporary Chicago and an off-site public exhibition of international artists to run during CAB, with the Graham Foundation to select emerging local architects to work with curator Katell Jaffres on the exhibition design. Such alignments have their advantages, however, EXPO Chicago is first and foremost about commerce, and while one might argue that architecture is too, I worry that profit and “festivalism” will supersede the productive experimentation that the axis of architecture and art can foster, and will favor exhibition over experience, spectatorship over participation.

Granted, this is just one component of a larger program, much of which is still to be determined. What is known publicly is that The Cultural Center will once again serve as the main hub; the design competition for students of local architecture schools will also be a component of the 2017 edition. For the inaugural biennial, students worked in collaboration with international architectural firms on a series of proposed lakefront kiosks as part of what CAB identified as its “legacy projects,” although to date none have been realized, with the exception of Chicago Horizon by Ultramoderne, winner of the BP prize and not part of the student competition.

Re-envisioning the legacy projects as a series of think tanks, where students work in tandem with established architects to realize solutions to real-life problems (e.g., temporary shelters for refugees and flood victims, rebuilding communities after war and natural disaster, environmental development, gun violence) would have more impact. As mentioned in my earlier post reviewing the first CAB, Jeanne Gang’s Polis Station, a re-mapping of the North Lawndale neighborhood in Chicago to curb police violence and build community relations, is one such example. In fact, establishing the whole of CAB as an incubator for architectural experimentation, research and advocacy, one that deftly balances a local/global vision, would define itself and the biennial model as something more than a showcase. Keep the locus at the Chicago Culture Center, but extend the biennial’s reach and presence into the city’s neighborhoods; involve communities throughout the planning process and often. Use the critical stance of the “off-modern” to, as Boym suggests, embrace the peripheral, make visible lesser-known traditions, create new affinities. Explore site-specificity in all its forms and permutations.

The Chicago art world is known for its spirit of collaboration, grass-roots politics and for defining art as a social practice; Chicago architecture for its invention and trans-disciplinary approach to architecture and design, as evinced by the New Bauhaus whose importance and legacy remain foundational and can be witnessed in the current exhibition “Moholy-Nagy: Future Present” at the Art Institute of Chicago (to January 3, 2017). It is within the realm of public space that art and architecture, as essential components of urban design, uphold and, sometimes, contest the political imaginary. CAB has the potential to do the same.

Notes

- See: http://chicagoarchitecturebiennial.org/2017/.

- Svetlana Boym, “The Off-Modern Condition,” http://www.svetlanaboym.com/offmodern.html. Accessed October 17, 2016.