To the River: More on the Art and Politics of Walking in the City

October 20, 2017 / 0 Comments

As I consider Chicago’s new Riverwalk, I am reminded of Bob Dylan’s oft-covered song “Watching the River Flow,” in which the song’s protagonist, lonely and alienated within an unidentified city, finds solace sitting along the sandy banks of an unidentified river. The song’s themes of inspiration and displacement, fostered by clashes between public and private, urban and nature, seem an appropriate metaphor for the inherent issues embedded within urban renewal projects that repurpose former industrial sites, including riverfronts, into green spaces. Related to my earlier post about New York’s High Line and Chicago’s 606 – urban revitalization initiatives that transform abandoned rail lines into cultural spaces for walking – I am interested in exploring the impact of these large-scale public works projects on the communities where they take place, and the promises of environmental renewal that they pledge. From the vantage point of creative placemaking, I am invested in a strong role for artists in the decision-making and design process, and the successful integration of environmental and spatial art practices into the everyday dance of the riverfront promenade.

Like the High Line and The 606, Chicago’s Riverwalk belongs to broad-scale redevelopment happening across Chicago and other cities in which new public greenways devoted to walking are central to urban renewal. Urban theorist Jane Jacobs saw sidewalks and neighborhood parks as essential to the public life of cities. She also advocated for development that transformed “border vacuums,” vacant, dead-end spaces along waterfronts, rail yards, expressways, and parking lots, into sites of active use or “seams.” Writing in 1961:

“It is more to the point to grasp the problem where it originates, at the shoreline and aim at making the shore a seam. Waterfront work uses, which are often interesting, should not be blocked off from ordinary view for interminable stretches, and the water itself thereby blocked off from city view too at ground level. Such stretches should be penetrated by small, and even casual public openings calculated for glimpsing or watching work and water traffic . . . . Boating, boat visiting, fishing and swimming where it is practical, all help make a seam, instead of a barrier, of that troublesome border between land and water.” (Note 1)

As Robert Kanigel argues in Eyes on the Street, his biography of this prophetic champion of cities, Jacobs did not readily embrace the New Urbanists, whose ideas have spawned some of these new pedestrian-oriented developments. (Note 2) However, I think that the Chicago Riverwalk fulfills some of the essential elements advocated by Jacobs, most notably in creating a seam between the river, the lakefront and the city. First initiated in the 1990s and completed last fall, this 1.25-mile pedestrian walkway follows the south bank of the Chicago River between Lake Michigan and Lake Street, integrating the city’s lakefront and riverfront into a continuous public park and pedway. The Riverwalk’s design, a collaboration between Sasaki Associates, Ross Barney Architects, and Alfred Benesch Engineers, transforms the riverfront into a series of black-long open bays, each with their own personality and purpose, among them floating piers for observing fish and plant life, a cove for kayaking, a zero-depth fountain for wading, and a vertical rise of stairs that provides seating for observing the “theater” of the river below. In my mind, the least successful of these spaces are those that house upscale restaurants, tiki bars and wineries, prioritizing commerce, tourism and rosé over recreation and reverie.

The Riverwalk is also part of a larger initiative (Great Rivers Chicago) to reclaim the Chicago, Calumet and Des Plaines rivers for the development of more recreational and economic opportunities for the city (often code for gentrification as the current, contested development along the Chicago River’s North Branch near the Goose Island industrial corridor portends), and to improve the overall health and ecology of these aquatic environments (storm and sewer run-off being one of the main pollutants). These goals, along with the creation of the Riverwalk as a continuous trail with public access, were at the core of “River Edge Ideas Lab,” a satellite exhibition of the current Chicago Architecture Biennial (September 16, 2017-January 7, 2018), which invited nine architects to re-envision the south branch of Chicago’s riverfront at three pivotal sites: the Civic Opera House, the Congress Parkway, and the Air Line Bridge at Chinatown’s Ping Tom Memorial Park. No doubt an audition for a future leading role, participating firms include Adjaye Associates, James Corner Field Operations, Perkins+Will, Ross Barney Architects, Sasaki, site, SOM, Studio Gang, and SWA.

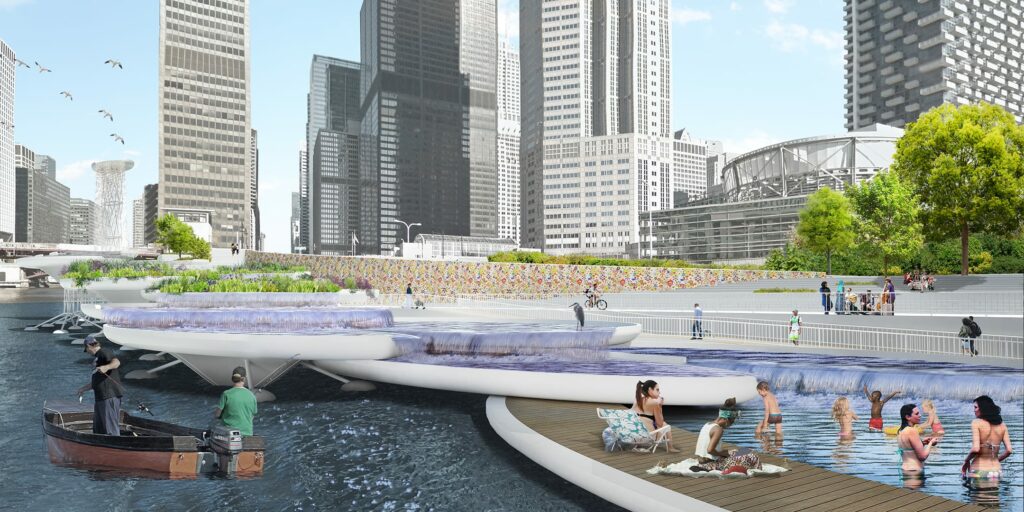

Several designs for the Air Line Bridge location respect the current ecology of Ping Tom Memorial Park, a 17-acre former rail yard and historic industrial corridor converted into a public park and restored prairie. Proposals include restored wetlands and habitats, increased spaces for kayaking and boat races, beaches for swimming, and a forested tree canopy. Proposals for the Congress Parkway site more openly address the environmental impact of vehicular traffic and other high-stress uses of this congested South Loop hub that currently severs access to public parks and the river. For example, Ross Barney’s Congress Filter (my favorite) is a system of waterfalls and raised platforms that aerate and filter river water while also providing shallow pools for swimming. SOM’s design similarly includes biofiltration waterfalls and windmill-driven pumps to aerate water, as well as a soundgarden.

Several visions for the Opera House edge transform this site into an outdoor amphitheater using the building’s large limestone façade as a screen for projecting films, moving images and lights. Floating platforms imagine stages for performances and additional seats for viewing; exterior opera boxes, proposed by Perkins+Will, would offer public views of the performances inside. However, I am more drawn to designs by Sasaki, SOM, and a few others that are less theatrical and more focused on problem-solving the difficult pedestrian access to this part of the river, with proposals that inventively create fluid, multi-tiered pathways and points of entry.

Although proposals for the Civic Opera stretch of the Riverwalk celebrate the performative nature of its site, art and artists, absent within the designs, appear to play little to no role in these possible futures for the Chicago River. However, in all fairness to the Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events and the city’s Public Art Program, no doubt public works will eventually occupy some of these spaces, as they currently do for the completed portion of the Riverwalk. Ellen Lanyon’s Riverwalk Gateway, the first permanent work commissioned in 2000, serves as a passage between the lakefront and the river. Here, twenty-eight ceramic panels narrating the history of the Chicago River flank both sides of a trellised walkway beneath the Lake Shore Drive bridge. Just east of Michigan Avenue is the newly commissioned Howlings (2017) by Candida Alvarez, known for her abstract paintings that combine camouflage patterns with personal symbolism. The artist reconceptualizes her paintings as a series of large abstract scrims, four polyester-mesh banners that provide a soft yet dramatic backdrop to this high-traffic area of the walkway.

Howlings is one of a few temporary works on view for the first time as part of the city’s Year of Public Art, which also includes Tony Tasset’s larger-than-life fiberglass deer feeding on a grassy knoll at the pedway’s west end, and Scott Reeder’s text-based fiberglass sculpture, Real Fake (2013). Gilded in metallic gold paint and installed at the northeast corner of Upper Wacker Drive and Wabash Avenue directly across from Trump Tower, its titular message offers the perfect political critique.

Courtesy Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas. Image by the author.

This summer, The Floating Museum, an artist collaborative that creates temporary, site-responsive art projects throughout Chicago neighborhoods, organized “River Assembly,” an industrial barge converted into a mobile art museum. Docked at various locations along the river, including the Riverwalk, this itinerant exhibition and series of public performances, workshops, and community events spun on the history of the Chicago River as an industrial waterway and as a physical site that transcends traditional city borders. One might see echoes of Robert Smithson’s Floating Museum and Andrea Zittel’s Indy Island, a floating habitat and residency created for the White River in Indianapolis, although River Assembly acted as more of a traveling Wunderkammer. Over thirty artists created works displayed inside wooden crates installed both on the barge and at designated sites on the Riverwalk and Navy Pier, operating as a kind of cultural cargo. Video and film works were also screened, and two oversized yellow busts of Jean Baptiste Pointe du Sable reclining on the barge’s platform commemorated this founder of Chicago who established the city on the mouth of the Chicago River.

Jacobs once proclaimed, “A city cannot be a work of art,” arguing that art and life are not the same, instead imbuing art with the power “to illuminate, clarify and explain the order of cities.” (Note 3) While I might disagree with her claim of the exclusivity of art and life I do acknowledge Jacobs’s notion that art offers a vision of the city that could inform city planners and designers, and “help people make, for themselves, order and sense, instead of chaos, from what they see.” (Note 4) Cultural theorist Rosalyn Deutsche similarly argues “[a]gainst aesthetic movements that design the spaces of redevelopment,” in favor of “interventionist aesthetics” and “public art as a spatial activity.” (Note 5) Within both their views are a myriad of possible public art models that could inform, intervene, and activate the evolving spaces of the Riverwalk, expanding upon the merits of the current public works on view.

One model might be the Milwaukee RiverWalk, a three-mile walking corridor along the Milwaukee River in the city’s downtown, in which New York-based environmental artist Mary Miss was a central player in the project’s development and design. Her related forthcoming public work WaterMarks makes visible the importance of water to Milwaukee through a series of site-specific installations that will transform new and existing vertical markers throughout the city into oversized map pins. Miss has worked with rivers in the past, including those in New York, Beijing and Indianapolis, as part of her City as a Living Laboratory, a project that includes her own works as well as collaborations between other artists and scientists.

Such projects belong to a broader practice of environmental art focused on helping communities, large and small, meet current ecological challenges, while raising awareness about the significance of rivers, lakes and waterways to the cultural life and health of cities. From pioneers of Land Art, including Miss, Agnes Denes, Newton and Helen Mayer Harrison, to contemporary eco artists Mel Chin, Mark Dion, Lillian Ball, Natalie Jeremijenko, and others, there is plenty of rich cultural history to build upon and current examples by which to establish creative partnerships that enlist and embed artists, as these pedestrian waterfront developments continue.

For theorist Michel de Certeau the city is experienced as a social rather than physical space through the everyday practice of walking. Thus future public art projects for the Riverwalk could also focus on artists for whom walking is a part of their practice and whose works directly engage the public as discoverers and wanderers. Like eco-art, walking art also has a long and varied history, from the Situationists’ dérive, a form of wandering or drifting that actualized the pychogeographical effects of walking in cities for social transformation, to the nature walks of Hamish Fulton and Richard Long, to Francis Alÿs’ Paseos and Janet Cardiff’s audio tours. Such projects reinterpret the everyday spaces of public life, offering others the freedom and opportunity to access the river and the city in ways that are both new and self-defined.

I have walked, biked, and once kayaked the Chicago River and return to the Riverwalk often. My experiences are neither spectacular nor sublime (I am not a romantic), but something a bit more personal and understated, dependent on the crowds, the weather, the state of politics in the city, my state of mind. The river and the Riverwalk will continue to grow and change; plans are already underway for a 312 RiverRun on the north branch of the Chicago River. As both a critic and a citizen, I remain committed to the cultural opportunities these pedestrian waterfronts offer, but for now I’ll just sit – or walk – and watch the river flow.

Notes

- Jane Jacobs, “The curse of border vacuums,” in The Death and Life of Great American Cities (New York: Vintage Books Edition, 1992), p. 268.

- Robert Kanigel, “Ideas That Matter,” in Eyes on the Street: The Life of Jane Jacobs (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2016), p. 371.

- Jane Jacobs, “Visual order: its limitations and possibilities,” in The Death and Life of Great American Cities, p. 375.

- Ibid., p. 378.

- Rosalyn Deutsche, “Uneven Development,” in Evictions: Art and Spatial Politics (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999), p.