Public Encounters in St. Louis

July 24, 2019 / 0 Comments

What is a public? According to theorist Michael Warner, “a public is understood to be an ongoing space of encounter for discourse,” a self-defined social space of dialogic interactions and interplays. For Warner, a counterpublic is similarly discursive but assumes a “conflictual relation to the dominant public,” by creating its own audiences and idioms through alternative forms of address. (1)

The idea of the “discursive public” forms the basis for Counterpublic, a new art triennial that reclaims the spatial environment of St. Louis as a body of distinct yet overlapping publics, each with their own cultural identity. Employing public art strategies as diverse as the communities from which they emanate, Counterpublic directly engaged the residents of the city’s Cherokee Street neighborhood through temporary commissions, performances, film screenings and communal events situated within the everyday spaces where people work and live. A lively nexus where four diverse neighborhoods intersect, Cherokee Street is an amalgam of creative ventures and family owned businesses serving the neighborhood’s majority Latinx , Black, and immigrant communities. It is also home to The Luminary, an experimental space for art and activism, and a leading voice for alternative culture in the region and beyond. Luminary co-founders Brea McAnally and James McAnally and curator Katherine Simone Reynolds organized the triennial as a forum for the exchange of ideas around immigration, citizenship and displacement using the Cherokee Street neighborhood as its subject and site.

Counterpublic was also created as an alternative to the growing number of biennials and triennials that have recently emerged throughout the Midwest, including the Chicago Architecture Biennial, Open Spaces in Kansas City, and Front International in Cleveland. Rather than emulating another large-scale event based on the rotating interests of outside curators and on established models that often prioritize cultural tourism over cultural investment, Counterpublic emanates from within the community. “We are adopting a triennial model but hijacking the language to do something different,” James McAnally told me. “Counterpublic is built from the ground up.”

Such ground-level projects have emerged in response to the current political climate and to life in post-Ferguson St. Louis, whose diverse communities – like those in cities elsewhere – have been significantly impacted by the pressing issues addressed by the triennial’s artists. However, in lieu of artworks that simply expose the social inequities and economic conflicts caused by public policy and uneven development, Counterpublic revealed how the public life of a city can be experienced in just a few blocks. Rejecting the notion of a single, unified public, the exhibition gave agency to the neighborhood’s often marginalized publics by offering varied platforms of engagement that bridged the divide between art and life. To this end, the triennial’s thirty-some works were sited in panaderías, small breweries, storefront windows and shops, as well as various outside spaces along a mile or so stretch of Cherokee Street. For local residents, these site-responsive interventions transfigured seemingly ordinary actions into subtle acts of resistance – what Michel de Certeau terms “the practice of everyday life” – as in Rodolfo Marron III’s customized cookies created for Diana’s Bakery with the words “Aquí Estamos” (We Are Here) and “No Nos Vamos” (We Won’t Go) scripted in colorful icing. Proceeds from the sale of the cookies benefit Latinos en Axión, a local nonprofit organization supporting Latinx rights.

The paper works of Fidencio Fifield-Perez layered the artist’s personal history as a DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) recipient onto the public mission of Bridge Bread, a nearby bakery that provides job opportunities for the homeless. Envelopes that once couriered the many documents needed to verify Fifield-Perez’s legal status become the canvases for a series of meticulously painted potted plants, seen here as symbols of home and rootedness. Memory, transience, and displacement are interwoven in the artist’s related work on view at the gardening shop Flowers & Weeds. Utilizing maps and traditional Oaxacan paper-cutting techniques, Fifield-Perez appropriates this Mexican craft form used in celebrations and for honoring the dead to construct an intricate tapestry that despite its delicate, painted structure is suggestive of the chain-link fences that separate the US-Mexico border.

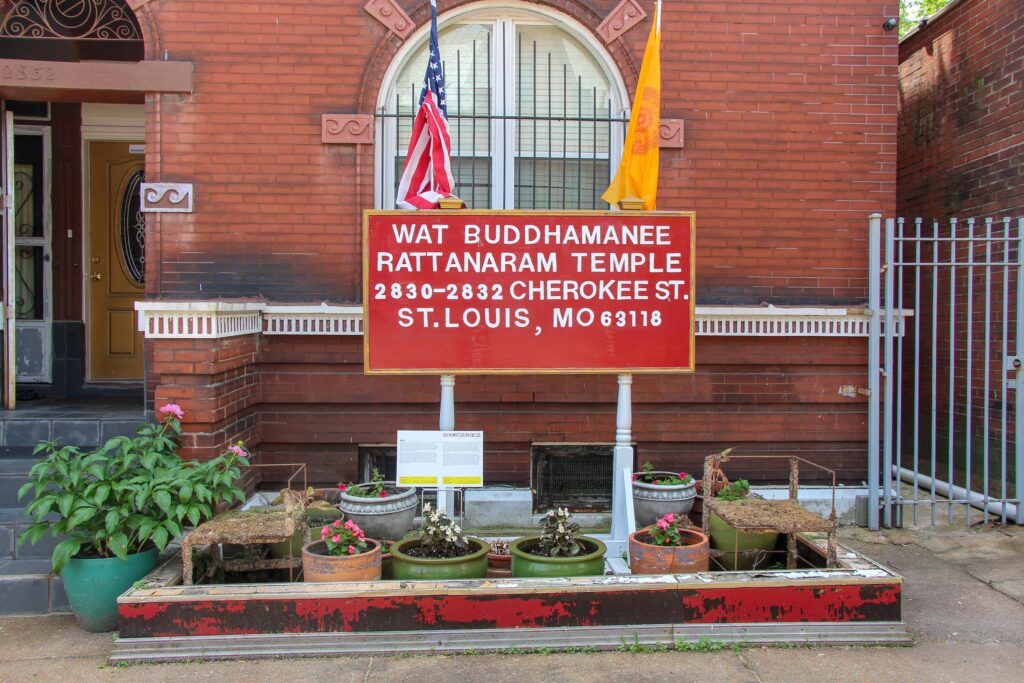

For this outside viewer, individual works were experienced either by happenstance – such as a pair of Donald Judd chairs crafted from birdseed by OOIEE (Office Of Interior Establishing Exterior) and seated amidst a small garden in front of a Buddhist temple – or as a kind of scavenger hunt. The latter resulted in varying degrees of reward given the embedded nature of many projects whose exhibition was dependent on the hours and inclinations of their host sites. Whether through the process of discovery or with the aid of a printed map, the most powerful works were those that served a commemorative function, among them Theodore Kerr’s wall of posters honoring Robert Rayford, a black, gay St. Louis youth, who was one of the earliest known victims of HIV/AIDS. Kerr, also a writer and activist, is one of several artists who created projects through the Luminary’s residency program. His wheatpasted posters layering images of Rayford’s home, newspaper clippings, the Silence = Death logo and other documentary materials was accompanied by a series of public programs addressing HIV/AIDS within St. Louis’s Black community.

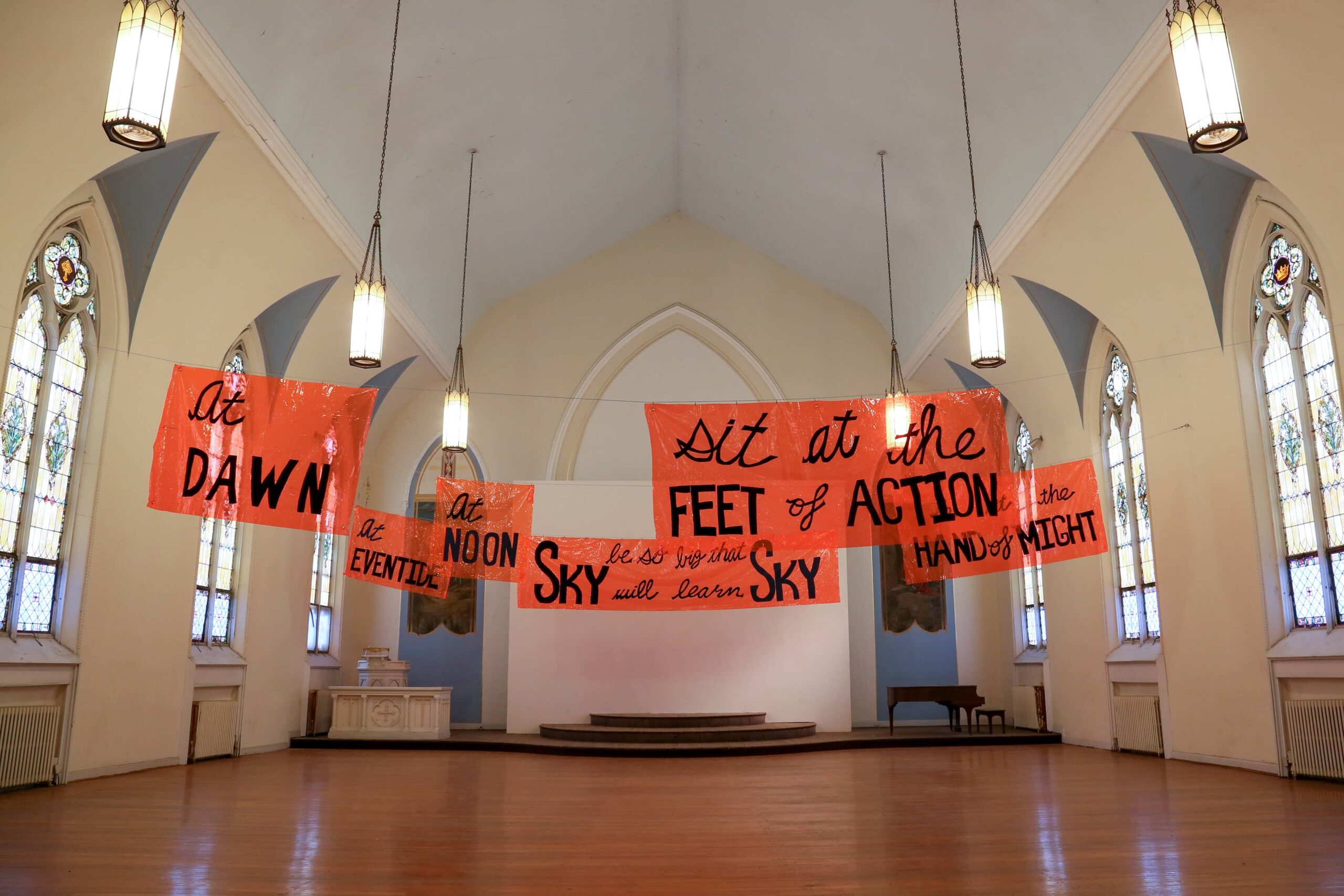

The power of historical memory in catalyzing today’s protest movements around Black lives was also central to Cauleen Smith’s elegiac Sky Will Learn Sky, an homage to Black spiritualism and one of Counterpublic’s most defining moments. Smith’s themes of the transformative power of art and mysticism filled a former church now punk club into a space for radical thought and communion as manifested in a two-part installation. Upstairs, six banners made of orange vinyl heralded excerpts from a text by jazz musician turned swamini Alice Coltrane, and from which the work takes its title. The translucent banners emit their own ecclesiastical presence within the church’s sun-filled nave; they also carry Coltrane’s words – part revelation, part call to action – throughout the accompanying film Sojourner (2018) on view in the church’s darkened basement. The film’s setting is Noah Purifoy’s desert assemblage museum in Joshua Tree, where a group of women gather to envision a feminist utopia based on the ideas of Coltrane and other figures of Black spiritual activism.

The traditional role of art museums and institutions in defining the cultural narrative of a city was put to question throughout the triennial. The installation Monuments, Ruins and Forgetting by Joseph del Pesco and Jon Rubin challenged how the history of a neighborhood is defined, particularly one in transition, and became somewhat emblematic of Counterpublic as a whole. The artists transformed a vacant store across the street from The Luminary into a revolving national museum of “monuments,” “ruins” and “forgetting,” using yellow and black signage that rotated on the building’s façade. The outside front entrance served as an informal stage for a series of musical performances, although the building remained empty throughout the course of the triennial’s three-month run. While at once a symbol of gentrification and displacement, the evolving installation presented itself as a new kind of cultural infrastructure whereby a neighborhood remembers and imagines its own history.

Questions of who owns and has rightful access to the public sphere of the city were posed in the mobile sound monument Not Peaceable and Quiet (Piñata Sound System), a collaborative project by Matt Joynt, Josh Rios and Anthony Romero. The artists outfitted a bike recuperated from a failed bikeshare program with colorful fringed duct tape and a trailer with a sound system that played an audio track of digitized cumbia music. The sonic sculpture filled Cherokee Street with a loud, rhythmic backbeat, an act of purposeful defiance against the stricture of noise ordinances that often police and dispel communities of color from urban public spaces. Counter to conventional monuments that sit inert and silent, this performative work became a monument to mobility, empowerment, and musical celebration when activated by visitors and residents who were welcome to ride the bike throughout the neighborhood.

Not Peaceable and Quiet was also the subject of a related discussion and podcast hosted by Monument Lab, a Philadelphia-based public art initiative devoted to rethinking public monuments. Currently in residence at the Pulitzer Arts Foundation, Monument Lab is facilitating a city-wide research project entitled Public Iconographies that solicits St. Louis residents to reflect on the past, present and future of its public markers and symbols. In addition to a series of community gatherings, the public is asked to submit proposals and hand-drawn maps that consider monuments both real and speculative for an upcoming atlas to be published this fall.

Both projects embrace the idea of listening as a means to connect to one’s community and environment. For the collaborative artists of Not Peaceable and Quiet, music transcends physical and geographic borders while also creating a sense of belonging. Public Iconographies mediates the dialogue on public monuments by catalyzing new conversations, productive argument, and in the words of Warner “interactive relations.” These are also the discursive tools at the heart of Counterpublic, which posits how art can create a space for social encounters in which lived experience supplants the homogeneous public sphere of “the city.”

Notes

Counterpublic was on view at various sites throughout the Cherokee Street neighborhood of St. Louis, April 13-July 13, 2019.

- Michael Warner, “Publics and Counterpublics (abbreviated version),” Quarterly Journal of Speech, Vol. 88, No. 4, November 2002, pp. 413-25.