Planting the Future City

April 9, 2020 / 0 Comments

As I have mentioned many times here and throughout my critical practice, Rosalyn Deutsche’s book Evictions: Art and Spatial Politics has been an endless source of inspiration for me. Deutsche centers her discourse on public art in political reinventions of public space, looking to radical definitions of democracy and to analogies that equate cities with biological systems. Such analogies are even more prescient given our current pandemic that heightens the realities of the interconnectedness of humans, cities, and ecosystems and the social, economic, and environmental injustices that result when those links are destabilized. [Architecture critic Michael Kimmelman of The New York Times has just written about the “anti-urban” nature of the coronavirus that erodes the very essence of cities – centers of commerce and creativity where the everyday is lived communally and in shared public spaces.] (Note 1)

Deutsche’s investigations of the complex and sometimes contentious relationship among art, politics, and public space have broadened my understanding of what constitutes a democratic public sphere, which for Deutsche is necessitated by conflict and plurality. Her definition of the city as a spatial environment produced by diverse groups in a network of social relations has led me to expand my own definition of public space to include Earth’s ecology. Thus, much of my recent writing has focused on spatial art practices centered on environmentalism in urban communities, from sculptural interventions that make publics aware of the impact of human activity on Midwest bird species (Jenny Kendler) to city-scaled projects that connect citizens to local water systems and ecologies (Mary Miss). Likewise, I’ve been interested in neighborhood development projects spearheaded by artists, in particular women, who employ community and systems-based approaches to urban agriculture to address a broad range of environmental and economic issues, including physical and mental health.

Civic practice artist Frances Whitehead has been a leading figure in this regard, bridging contemporary art, civic engagement, and the discourse on climate change to create an integrative art of placemaking. In her pioneering works and writings, she positions the artist as an active agent in civic projects centered on sustainability and environmental renewal, asking What Do Artists Know? as the basis for innovative thinking, creative problem-solving, and unique knowledge skills. In her role as lead artist for Chicago’s Bloomingdale Trail (The 606), an adaptive-reuse project that repurposed an abandoned railway into an elevated greenway on the city’s northwest side, Whitehead proposed and facilitated designs solutions throughout the trail and adjacent parks, including the astronomical observatory at the western trailhead. A central component of The 606 is the phenological planting of flowering trees (native serviceberry and lilac shrubs), a living artwork developed by Whitehead. In addition to providing the near three-mile trail with spectacular blooms, the trees allow citizen-scientists to monitor the fluctuating temperatures of Lake Michigan on the seasonal patterns of the trail’s landscape. (Phenology is the study of animal and plant life cycles in relation to the seasons and the weather.) Over time, their recorded observations will serve as a database for understanding Chicago’s micro-climates and the impact of climate change.

Whitehead’s most recent project, Fruit Futures Initiative Gary, is a multi-tiered community orchard project in Gary, Indiana, that provides food access and economic development to this post-industrial city plagued by a whole host of racial, economic, and environmental injustices. Working with neighborhood residents and the City of Gary, Whitehead is transforming vacant lots into foodsheds for fruit trees, engaging community members in planting, maintenance, and research, while they develop long-term stewardship and a sense of civic pride. A micro-orchard is the investigative site for exploring soil health and testing which fruiting trees and shrubs will thrive. According to the artist, Gary’s underlying soil consists of ancient sand deposits, an ecology hospitable to various fruit cultures, including gooseberries, raspberries, grapes, plums, and pears. Similar to the phenological planting of The 606, ornamental trees planted along the Broadway Street bus route will serve as visual indicators of climate and seasonal change and beautify the city’s downtown. For Whitehead, art becomes the interface between scientific and community forms of knowledge as well as the catalyst for regenerative design strategies that reimagine the future city, including Gary, for the common good.

The ecological practices of Chicago-based artists Sara Black, Melissa Potter, and Nance Klehm similarly engage broad publics in environmental issues and awareness through soil remediation, urban foraging, plant rehabilitation, and communal forms of gardening. Utilizing the time-based processes of carpentry and woodworking, Black’s materials-centered practice often rehabilitates diseased woods transforming them into quasi-architectural structures and sculptural objects that offer alternative narratives of human impact on the environment. In several works, she employs “the process of carbonization to reveal the elemental existence of carbon in lumber,” a material long extracted for human consumption but whose expressions of resiliency and new-found utility challenge human-centered notions of nature and ecology (Note 2) In collaboration with Amber Ginsburg, Black constructed 220 wood benches which were later transformed into charcoal then biochar – a material that promotes soil biodiversity and long-term carbon storage. The project was created under the auspices of Wormfarm Institute, a cultural and artist residency program in rural Reedsburg, Wisconsin, devoted to art and agriculture, through which the artists conducted public workshops and disseminated biochar to local farms.

Working alongside scientists and environmentalists at the Landes-Hill Big Creek Reserve in California, the artists created 7,000 pencils from a felled tanoak tree infected with Sudden Oak Death in their ongoing project 7000 Marks (2016-), an homage to Joseph Beuys’ 7000 Oaks (1982), in which he planted 7,000 oak trees in Kassel, Germany, as part of documenta 7. As the artists have stated, “Planting a tree poses a solution. Making a pencil offers a speculative tool.” (Note 3) The pencils circulate through exhibitions and collaborative drawing and writing workshops that also enable participants to learn about broader environmental issues, reframing Beuys’ ideas about the regenerative potential of art in the context of today’s Anthropocene.

At the core of Melissa Potter’s interdisciplinary practice is a belief in the political potential of handcraft, with its rich and complex histories related to women’s labor and gendered ritual, in addressing ecological concerns. During her three-year collaboration with Chicago’s Lurie Garden, a 2.5-acre garden habitat in Millennium Park, Potter sources prairie grasses for her own papermaking practice and as educational material for her papermaking courses at Columbia College Chicago, where she teaches. Her ongoing project Seeds InService, a collaboration with Maggie Puckett, plants gardens from endangered seeds to grow fibers for hand papermaking. Exhibitions and public workshops become spaces for community artmaking, education, and research on sustainable food production in land-challenged urban spaces, and distribution of heirloom seeds through handmade paper books. Central to Seeds InService’s activities is the sharing of stories about women as makers, activists, gardeners, and agriculturalists – who like seeds are the givers of life – these feminist histories are compiled alongside a survey of the collaborative’s work in their recent, self-published book An Illuminated Feminist Seed Bank (2019).

Just as seeds are fundamental for growing the plant and food sources our planet needs to survive, so too is the soil that nurtures them. Soil is also the material that fuels the work of artist, author, and ecologist Nance Klehm, whose wide-ranging projects – including site-specific interventions that analyze the soil ecology of a given place and installations of decomposing materials that will later serve as compost – connect publics to the earth beneath their feet. Her lectures and workshops teach participants how to convert organic waste into nutrients for making healthy soil; in her urban foraging walks, citizens learn and sample the medicinal and edible plants found in urban landscapes. For Klehm, cities become diverse spatial fields for creative inquiry that reconnect citizens to the environment and to each other. “Who does this land, this place, this city and all its layers – open sky, tree canopy, shrub layer, grasses, forbs and crops, topsoil, subsoil and bedrock belong to?,” she asks. “Can we get back to this understanding of shared space as increasingly urbanized animals? It’s possible.” (Note 4)

The idea of place as a habitat for all life forms connects to the ideas of Bruno Latour, a key figure in today’s discourse on the environment, in particular our understanding of the interdependence between human and non-human entities and the distribution of resources among them. Latour expands the ideas set forth by the deep ecology movement of the 1970s that early on recognized the value of all living things and the need to sustain Earth’s richness and diversity. As I have noted elsewhere, his “actor-network” theory positions the human and natural world in a shifting network of relations, calling for a fundamental rethinking of how human and natural agents inhabit Earth. “We are not seeking agreement among all these overlapping agents, but we are learning to be dependent on them. No reduction, no harmony,” writes Latour. “The list of actors simply grows longer; the actors’ interests are encroaching on one another; all our powers of investigation are needed if we are to begin to find our place among these other actors.” (Note 5)

Just as “deep ecology” and Latour’s “actor-network” theory have fundamentally defined the discourse on climate change, so too have “deep engagement,” networked practices, and cross-disciplinary collaboration become foundational to today’s environmental art. Here, the city becomes the experimental ground where solutions to today’s challenges, including climate change, are tested through creative partnerships that include artists, architects, scientists, citizens, and neighborhood stakeholders. The collaborative, hybrid nature of these spatial art practices redefine the boundaries of disciplinary fields, contributing new kinds of dialogues to the discourse on art and the environment in the Anthropocene.

Such practices also belong to various lineages of Land Art, as I was reminded by the recent exhibition of the work of Agnes Denes (Absolutes and Intermediates at the Shed, New York), whose Wheatfield – A Confrontation (1982) remains one of the earliest and most iconic public works to address planetary distress through urban agriculture. Denes planted a two-acre wheat field in a landfill created when New York’s World Trade Center was built, converting material waste into fertile soil into wheat. Situated against the backdrop of the Twin Towers (former symbols of world trade and commerce) and facing the Statue of Liberty to the south, Wheatfield confronted the economic contradictions and social inequities embodied by the work’s site and modeled a new art form. The artist maintained the field over a four-month period, eventually harvesting over 1,000 pounds of golden wheat, which traveled to almost 30 cities around the globe in an exhibition about world hunger. Seeds from the project were free to the public and the hay was donated to the city’s mounted police for their horses.

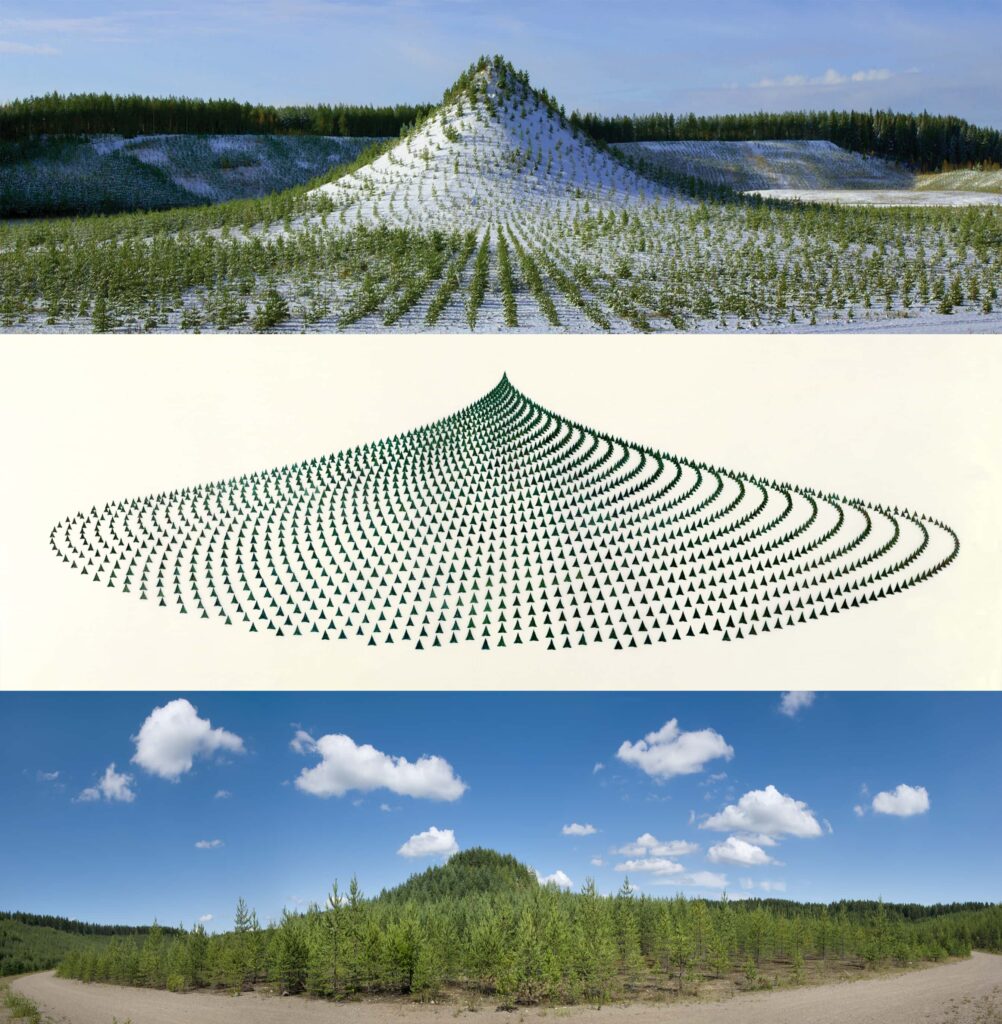

Wheatfield was documented in the Shed exhibition through photographs and a television interview with the artist and broadcast journalist Jane Pauley in a section devoted to Denes’ other public works, including Tree Mountain – A Living Time Capsule – 11,000 Trees, 11,000 People, 400 years (1992-96). The artist reclaimed a gravel pit in Finland by planting 11,000 trees in the shape of a large elliptical mound to create a forest that today has become one of the largest reclamation sites in the world. Denes has proposed a similar project for the Edgemere landfill in Queens, the speculative designs for which were on view alongside other unrealized projects.

Apparent here and throughout the exhibition is Denes’ prophetic and unique vision that has always combined scientific principles, philosophy, and aesthetics to address ecological issues and imagine possible futures – in the case of Tree Mountain, a virgin forest that will live for centuries. The future city is also the subject of the artist’s Pyramid Series (1970-), comprised of sculptures, drawings, and prints exhibited in the second-floor gallery, which also included two monumental models commissioned by the Shed. Here, Denes translates mathematical equations and linguistic ideas into transcendent, light-filled pyramidal forms that suggest alternative architectures for Earth’s adaption and human introspection.

For Denes, “the artist offers benign problem-solving for the challenges of the world,” as stated in a video that accompanied her public projects. In one passage, Denes offers the image of an octopus as a visualization for how artists create meaning, an image that still resonates with me. Paraphrasing her words: the main body of the octopus is knowledge; the tentacles are individual specializations; the role of art is to make connections.

These are just a few of the diverse array of collaborative approaches by which artists employ urban agriculture to foster connectivity, help us visualize the challenges of the present, and reimagine alternate futures. Some of these examples were also presented in an introduction to a panel I moderated last November as part of symposium at Bradley University on Midwest women artists working environmentally. (Note 6) The panel, Art Embracing Science, included Frances Whitehead and Sara Black to which I posed the following questions: How do you define our current environmental epoch? Given the dire conditions of today’s climate crisis, how do you sustain a sense of purpose? Whitehead suggested indigenous philosophies of place that reject universalizing terms such as the Anthropocene and invert the Euro-Western hierarchy of human over nature, referencing Maori walking practices she encountered in her various residences in New Zealand and that inspired her recent series of plant and map drawings. Instead, the locus of agency is found in deep rootedness to place and knowledge of local ecologies.

Black invoked the idea of Earth in hospice in which the role of artists (and all humankind) is to provide the planet with comfort and care. One might equate such an approach to our current pandemic whereby we are called upon to live respectively and mindfully both for ourselves and for others. While adopting a palliative approach to the environment assumes the inevitable, it also allows for planetary repair, as witnessed by the return of various wildlife to city streets and waterways during the Covid-19 quarantine. “Every place is the story of its own becoming,” states artist Newton Harrison, noting how after environmental catastrophe, every place regenerates its own ecosystem with new and resilient species adapting to altered conditions. (Note 7) The varied ecological practices of artists for whom soil and seed are material and agriculture a mode of production offer diverse paths towards climate adaption and regenerative development, planting the future city to come.

Notes

- See Michael Kimmelman, “Can City Life Survive Coronavirus?,” The New York Times, March 17, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/17/world/europe/coronavirus-city-life.html?referringSource=articleShare. Accessed March 30, 2020.

- As stated by Sara Black, see http://www.sarablack.org/about/. Accessed March 30, 2020.

- Sara Black and Amber Ginsburg, “7000 Marks,” in Antennae, Issue 44, Summer 2018, page 68.

- Nance Klehm, “Introduction: Citizen Animal,” in The Soil Keepers: Interviews with practitioners on the ground beneath our feet (Chicago: Terra Fluxus Publishing, 2019), p. 6.

- Bruno Latour, Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime, trans. Catherine Porter (Cambridge, MA: Polity Press, 2018), p. 87.

- The symposium Midwest Women Arts Champions of the Environment: 1960s to the Present took place at Bradley University, Peoria, Illinois, November 7-8, 2019.

- Newton Harrison as stated in a lecture presented at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, April 9, 2019.