Mapping the Waterways of Milwaukee with Mary Miss

October 21, 2019 / 0 Comments

The topography of the Upper Midwest is a patchwork of farms, prairies, flatlands, and large urban and industrial centers, diverse natural and built environments intimately tied to the Great Lakes and the region’s rivers. Within the current discourse on climate change, the impact of hurricanes and other environmental hazards upon coastal areas has somewhat overshadowed similar threats to inland communities and habitats. This year, excessive rainfall and swollen tributaries, many feeding into the Mississippi River, have devastated Midwest farmlands and river towns in what has been declared the Great Flood of 2019. Likewise, the waters of the Great Lakes are rising at unprecedented levels, altering ecosystems, eroding shorelines, and damaging housing and urban infrastructure. At the same time, the Great Lakes continue to provide North America with nearly 90% of its fresh water supply, with cities like Chicago and Milwaukee that border Lake Michigan spearheading efforts in water protection and stewardship.

With the goal to help the citizens of Milwaukee learn about the importance of water to the life of their city, artist Mary Miss has embarked on WaterMarks: An Atlas of Water for the City of Milwaukee, a multi-year project that fosters community and municipal partnerships to create public awareness around climate change. Known for her large-scale public art works centered on environmentalism in urban communities, New York-based Miss is a leading figure in spatial art practices that bridge sculpture, landscape design, architecture, and urban planning. Assuming the role of facilitator and creative protagonist, Miss takes a collaborative, interdisciplinary approach to sustainable development under the rubric of her City as Living Laboratory (CALL), a series of artist-led projects that connects local citizens, community stakeholders, scientists, and government agencies to address the environmental challenges facing cities.

Miss has addressed environmental issues throughout her significant career, from her earthworks and public art works of the late 1960s, 70s, and 80s to recent, urban-scaled projects like WaterMarks. These early works—encompassing outdoor interventions, temporary sculptures, wooden pavilions and walkways—operated within “the expanded field” of contemporary art that disrupted the structural parameters of sculpture, landscape, and architecture, as explored by Rosalyn Krauss in her iconic essay “Sculpture in the Expanded Field,” which includes Miss.

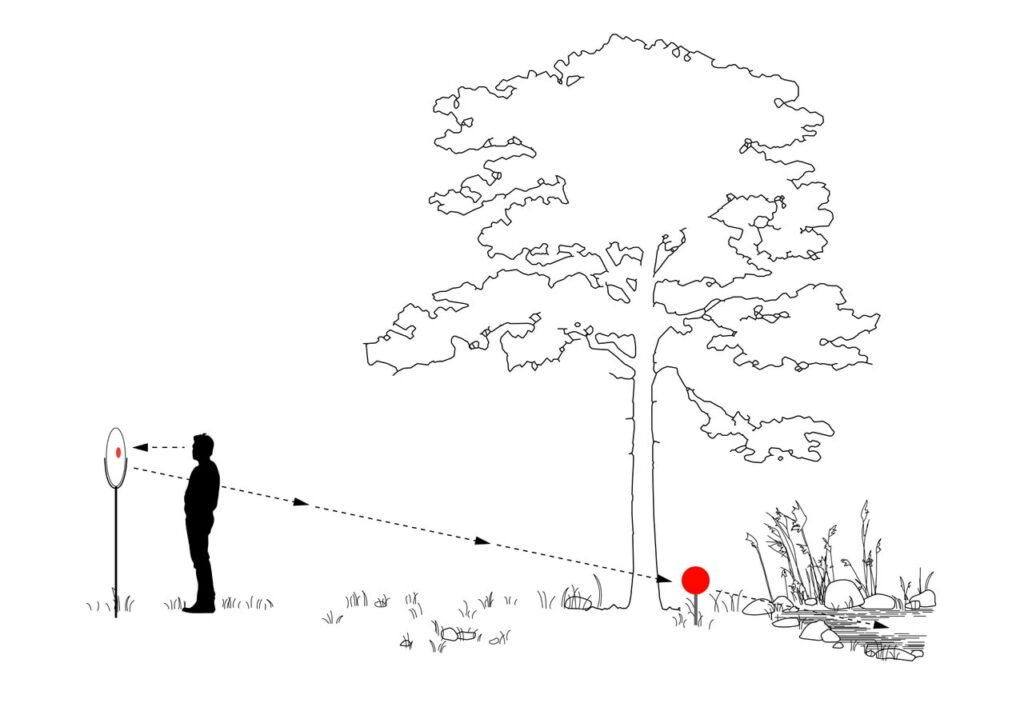

Rivers and waterfronts figure prominently throughout Miss’s diverse, ecological practice. FLOW: (Can You See the River?) (2008-11), the first project in the artist’s CALL series, has served as a prototype for other CALL projects, including WaterMarks. Commissioned by the Indianapolis Museum of Art for its Art and Nature park (the museum and its campus have been renamed Newfields), FLOW made visible the importance of the White River to the city of Indianapolis. Here, approximately 100 markers were installed along a six-mile stretch of the White River that extends from the museum to downtown Indianapolis. Half of the markers were painted red to simulate map pins; the other half took the form of circular mirrors etched with informational texts and red dots corresponding to physical and digital mapping systems that connected viewers to the ecology of the White River and surrounding landscape.

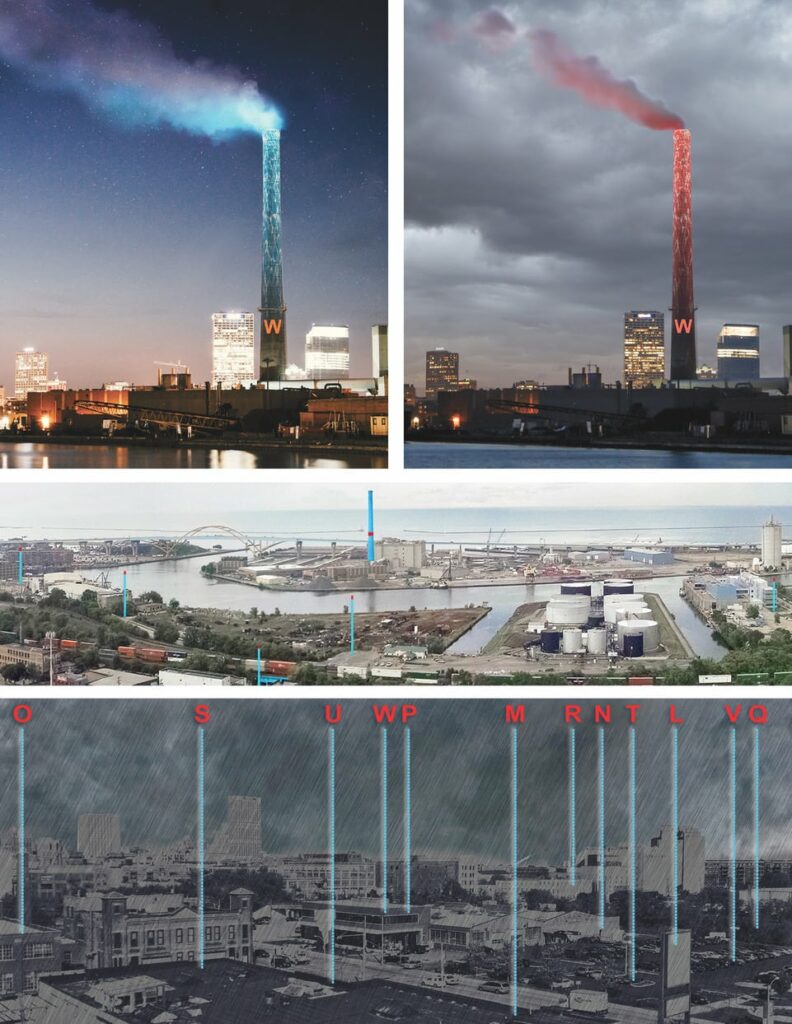

True to CALL’s mission, WaterMarks similarly brings water awareness to Milwaukee, in what is conceived as a visual and conceptual atlas that maps water resources throughout the city. It also builds on Miss’s previous collaboration with the city in 1998-2001: the extension of Milwaukee’s Riverfront walkway to the downtown Historic Third Ward for which she created the preliminary designs. Originated in 2015, WaterMarks will unfold over the course of several years, with the project’s initial phase to focus on the Inner Harbor District, where the Milwaukee, Menomonee and Kinnickinnic rivers converge and flow into Lake Michigan. This is also the site of the Jones Island Water Reclamation Facility that treats billions of gallons of water each year for the Greater Milwaukee and southeastern Wisconsin region. The plant’s smokestack rises 350 feet skyward and, when repurposed by Miss, will serve as WaterMarks’ central locus and beacon. To be equipped with a lighting system that will alert local citizens of impending rainfall, the stack will shine blue when the weather is clear and signal red when the forecast calls for rain, encouraging residents to reduce their water usage to help contain overflows of contaminated water.

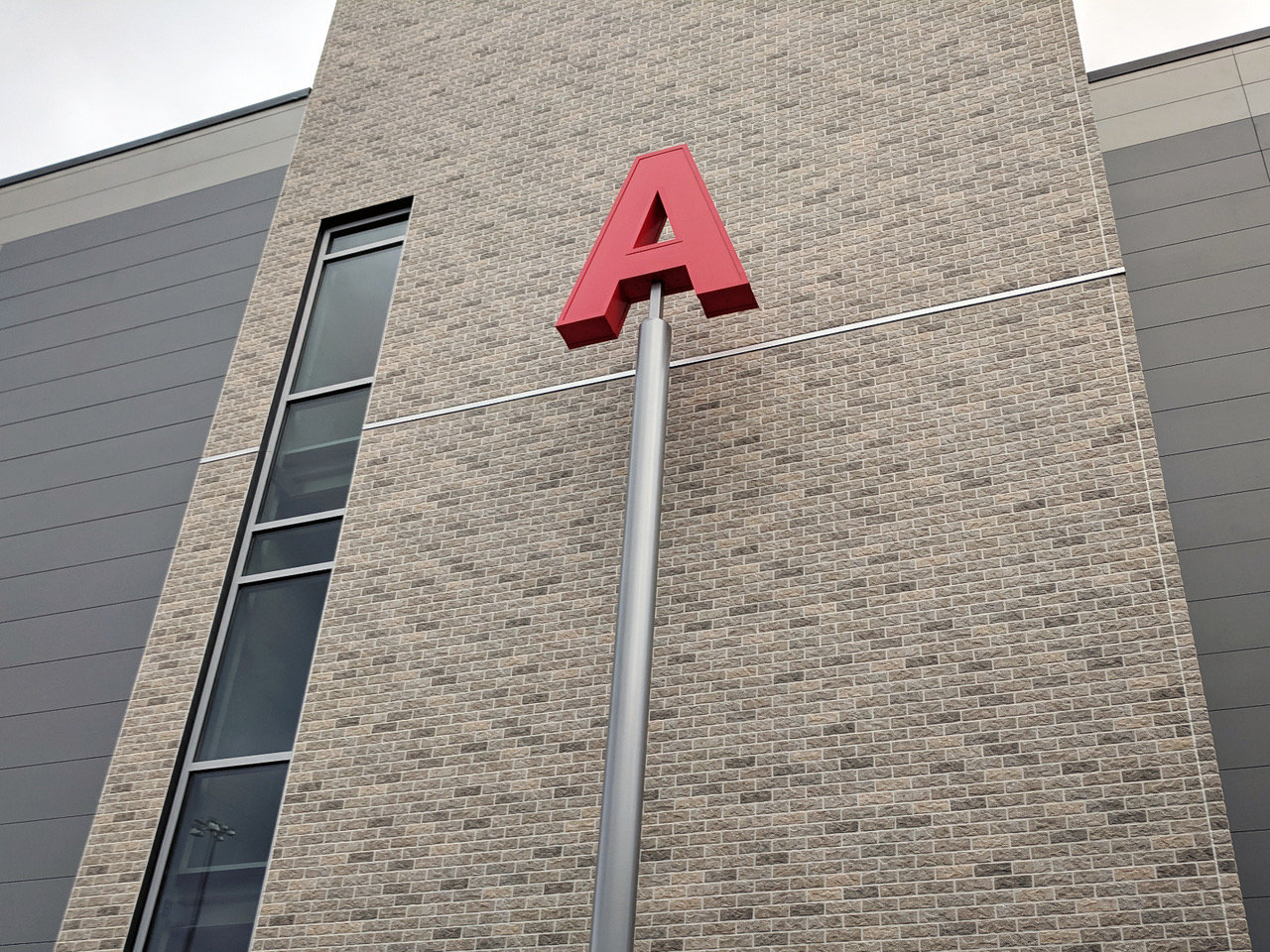

Other project components respond to the Jones Island installation and will be sited in neighborhoods as well as redevelopment zones marked for environmental remediation. Among WaterMarks physical elements is a series of Vertical Markers, aluminum poles measuring between 25 and 40 feet, to be installed at locations across the city related to the story of water in Milwaukee. A single, illuminated red letter will be placed on top of each Vertical Marker (the Jones Island Marker, for example, will bear the letter “W”), transforming the poles into oversized map pins that plot a new cartography of water for the city. The first of these makers, realized in 2018, now stands in front of the UCC Acosta Middle School, a nonprofit technology and skilled-trades charter school predominately serving the city’s Latinx population. Through classroom projects and public workshops, students, local residents, and community partners shared water stories and explored water infrastructures in the neighborhood, then selected the letter “A” (Acosta, agua, A+, art) to represent their school and stand atop the marker.

The Vertical Markers not only create a unified iconography for this citywide project, but also build the foundation for new green infrastructure that supports and makes visible Milwaukee’s water system. They also extend the project’s reach beyond the downtown Riverfront to underserved and underinvested areas of the city, and to those disproportionately affected by climate-related catastrophes, including flooding and contaminated water. One such area is Milwaukee’s 30th Street Corridor, once an industrial hub and economic engine for the city and now a vacant brownfield site, slotted for environmental remediation.

The vision for the 30th Street Corridor and its current revitalization were the subject of a neighborhood walk organized by CALL and Jane’s Walk Milwaukee, the latter an international festival of citizen-organized walks named for urban theorist Jane Jacobs. I joined the walk on a cool spring day last May, where we gathered on what appeared to be a neglected parcel of land within a desolate industrial strip. What I discovered, instead, over the course of the 1.5-mile walk—led by artist Portia Cobb and environmental engineer Tory Kress (and accompanied by Miss)—was a site rich with possibility. Known as Green Tech Station, this partnership of the Northwest Side Community Redevelopment Corporation and the City of Milwaukee will transform the area into green infrastructure and an educational greenspace. Soil grading and tree planting happened last year with funds from an EPA Clean Up Grant; future plans call for educational signage, a walking path and public art. Already in place is a stormwater management system, a large rectangular basin layered with crushed stones and equipped with four bioswales to clean water and a cistern to store rainwater. AquaBlox help store and filter water, and also become seating to configure the space as an outdoor classroom for environmental education. After sharing the ways in which water nurtures and sustains us, we walked to Century City and learned about initiatives to remediate blight and cleanup groundwater contamination at this 84-acre site, a former automotive factory to be converted into a new business park. We then proceeded to a nearby residential neighborhood to hear from residents about grass-roots efforts to transform a local park.

Workshops, walks, public events, and collaborative projects led by local artists will similarly activate additional sites, allowing communities to come together and identify their own priorities and wants. Other components will include digital apps that indicate marker locations and offer ongoing project information. These various forms of mapping are part of WaterMarks’ extensive community engagement program to raise public awareness around water and to share common goals for sustainability.

In Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime, French philosopher and anthropologist Bruno Latour argues for the necessity of on-the-ground, networked solutions to fight the current political challenges that thwart and deny the realities of climate change. “To resist this loss of a common orientation,” he writes, “we shall have to come down to earth; we shall have to land somewhere. So, we shall have to learn how to get our bearings, how to orient ourselves. And to do this we need something like a map of the positions imposed by the new landscape within which not only the affects of public life but also its stakes are being redefined.”(1)

Latour’s “actor-network” theory positions the human and natural world in a shifting network of relations, “in which all entities—air, soil, water, animals, and humans—are actors with agency.”(2) A network approach is the hallmark of CALL and Miss’s practice, which enlists a “constellation of heroes” and multiple visions reflective of the complexities and challenges of climate change through creative alliances.(3) This constellation includes artists, scientists, residents, city officials, and institutional partners, who through a process of deep engagement provide the knowledge and tools for individual communities to take ownership of each project.

Integral to the success and ongoing sustainability of CALL’s ambitious projects is responding to the specific needs of its respective sites, and connecting local citizens to city ecosystems and infrastructures. “Urban-scale projects are about systems,” Miss told me. “One of my strengths is the capacity for synthesis. I can chart a path through a complex situation.” A part of this path is to decipher complex environmental issues and make them tangible to broad publics. So too is disarming the “eco-anxiety” and language of fear around climate change to construct narratives of hope and empowerment without denying the realities of the challenges ahead. Merging aesthetic, scientific, and citizen-generated forms of inquiry, WaterMarks maps a way toward environmental renewal, operating at both “the scale of the city” and, in the words of Jane Jacobs, “with eyes on the street” to create a macro-micro view of the water ecologies of Milwaukee.

Notes

1. Bruno Latour, Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime, trans. Catherine Porter (Cambridge, MA: Polity Press, 2018), p. 2.

2. Bruno Latour as quoted by Maria Patricia Tinajero, “Ethical grounds: the aesthetic actions of soil, in Art, Theory and Practice in the Anthropocene, ed. Julie Reiss (Wilmington, DE: Vernon Press, 2019), p. 88.

3. Mary Miss, “Creating a New Narrative About Climate Change: 1000 Steps,” in The Brooklyn Rail: https://brooklynrail.org/2019/06/criticspage/CREATING-A-NEW-NARRATIVE-ABOUT-CLIMATE-CHANGE-1000-STEPS.

[…] (Jenny Kendler) to city-scaled projects that connect citizens to local water systems and ecologies (Mary Miss). Likewise, I’ve been interested in neighborhood development projects spearheaded by artists, in […]