Women at War gathers the works of twelve Ukrainian artists who employ a variety of media to address the Russian war against Ukraine, from its beginning in 2014 to the full-scale invasion in February 2022, through the lens of gendered experience. The exhibition explores the struggle for Ukrainian independence and women’s equality against the backdrop of the war and its impact on both the national and individual psyche while giving voice to women as narrators of history and agents of change. Curated by Monika Fabijanska, Women at War premiered at Fridman Gallery, New York, in the summer of 2022, and continues its North American tour through 2025.(1) I recently spoke with Fabijanska, known for her critically acclaimed exhibitions focusing on women and women’s art, about the challenges of organizing an exhibition about war alongside the show’s many themes of loss and resiliency, national identity, and feminism.

A new dialogue with curator and scholar Alexandra Midal on Ken Isaacs’s Knowledge Box and his search for an experiential model for education. Read the interview online

For Chicago-based, Puerto Rican–born artist Edra Soto, home is a psychic,

geographic place as well as a locus for gathering and community. It is also a

political space that defines who we are as civic and social beings. The complex

relationships between citizenship and migration, displacement and belonging,

inform the impressive suite of sculptural installations comprising

“Destination/El Destino: A Decade of GRAFT,” an unconventional survey

celebrating ten years of this ongoing project by Soto.

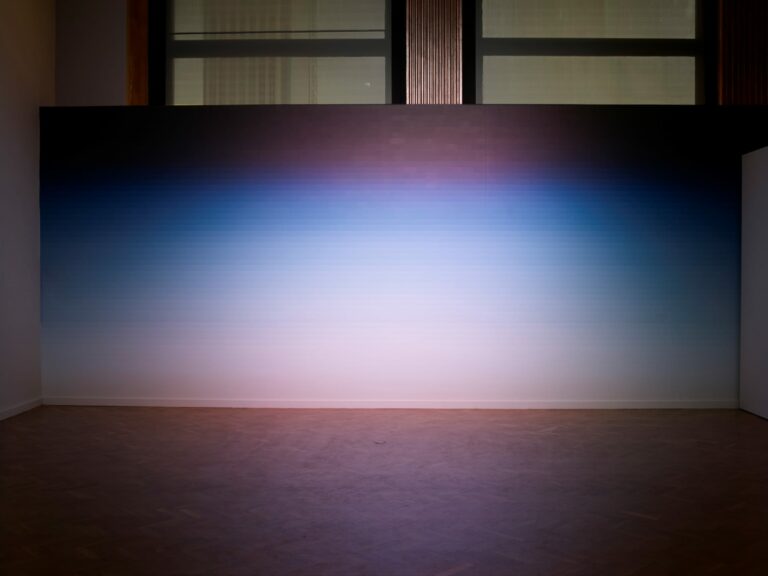

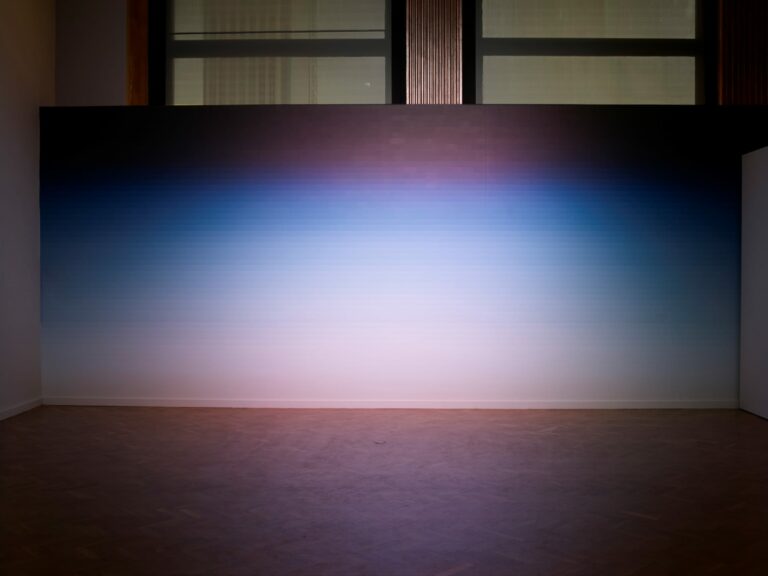

“Color is the most relative medium in art,” according to Josef Albers. Its relativity, along with the subjective nature of visual perception, forms the basis of the immersive light installations that comprise “Exact Dutch Yellow,” the most recent exhibition of Chicago-based collaborative Luftwerk (Petra Bachmaier and Sean Gallero), who transformed the fourth-floor galleries of this cultural institution into an oasis of complex optical phenomena.

Here I talk with Maria Kruglyak about my curatorial work and writing on Ken Isaacs, occasioned by the multiplatform mapping project Visual Natures: The Politics and Culture of Environmentalism in the 20th and 21st Centuries, organized by the Museum of…

Shunning mere esthetic representations of industrial ruin, the strength of Chris Larson’s project is the artist’s deep engagement with the material conditions of the factory itself—from its textile remnants to its architecture to its deserted machinery—and with the residual traces of human labor that such objects bear.

At once a celebration of beauty in all its opulence and material forms, Nick Cave’s Forothermore, the artist’s largest museum survey to date, is also a eulogy to Black lives lost to police violence and those harmed by societal bigotry and racism.

A new memorial project in Budapest, Memory of Rape in Wartimes: Women as Victims of Sexual Violence, will commemorate female victims of wartime rape, while establishing a culture of dialogue around rape and violence in Hungarian society and the region. In the following interview, art historian and critic Edit András discusses the origins of the memorial, the process for vetting proposals, and how contemporary public memorials to collective trauma should be conceived.

ŠTO TE NEMA (Where have you been?) by Bosnian-born artist Aida Šehović is an annual nomadic monument to the victims of the 1995 Srebrenica genocide that has traveled internationally to 15 different cities from 2006 to 2020. This participatory public monument, consisting of more than 8,372 fildžani (small porcelain coffee cups) that have been collected and donated by Bosnian families from all over the world, addresses issues of trauma, healing, and remembrance.

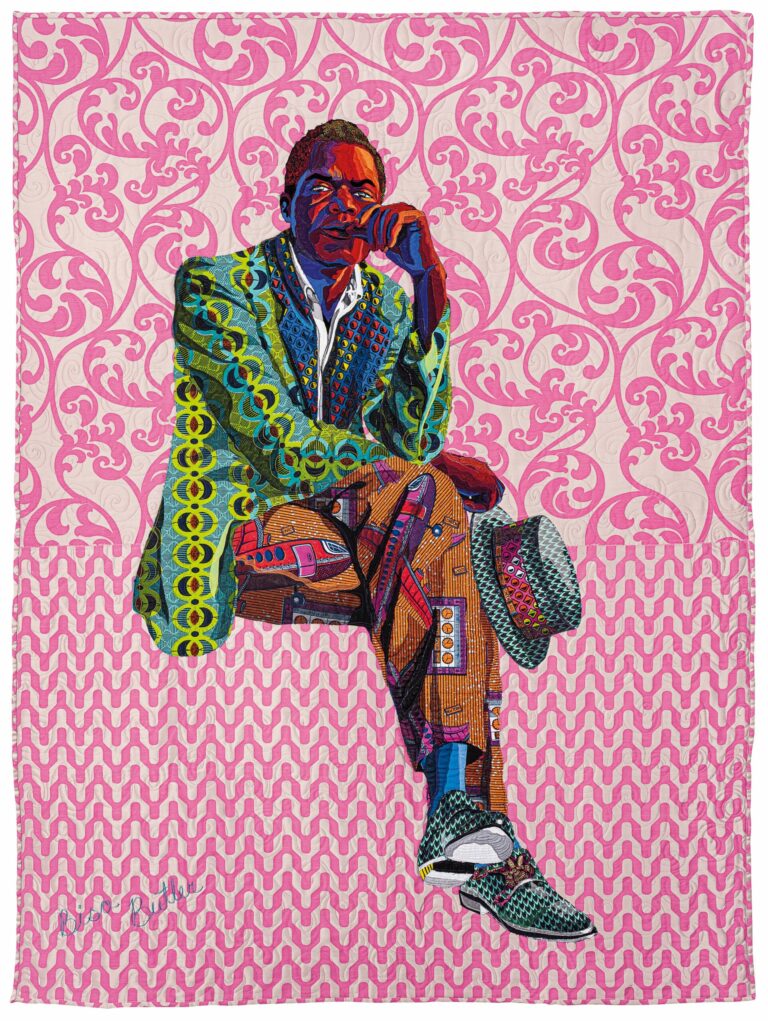

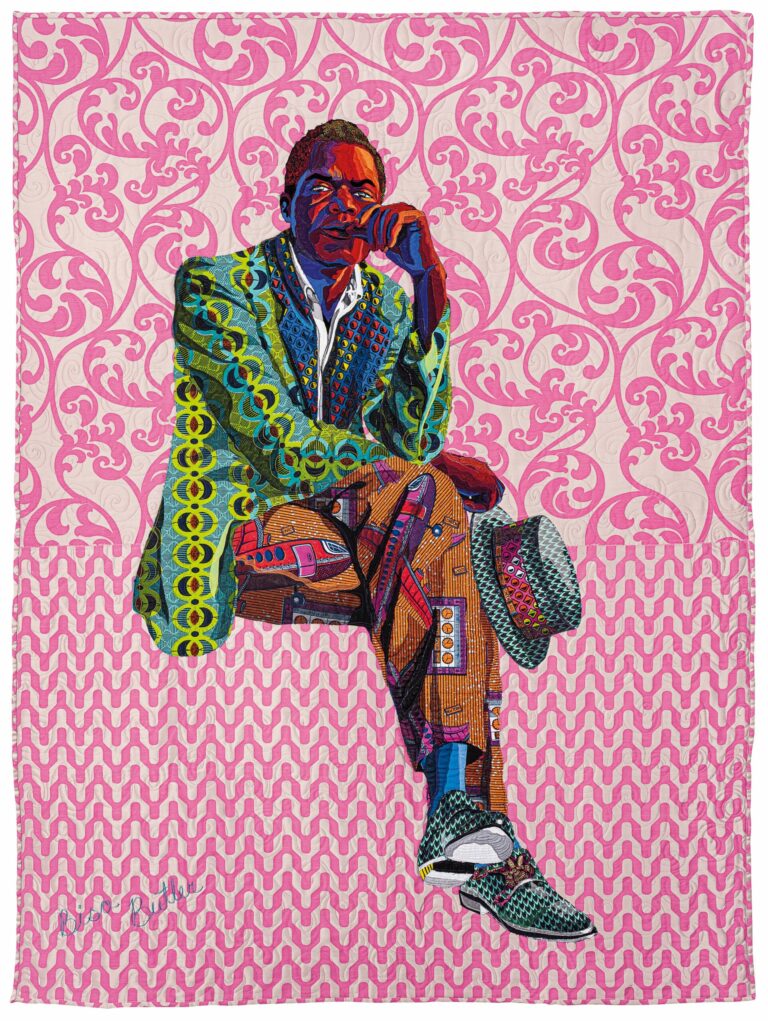

The subjects who populate the 22 quilts that comprise Bisa Butler’s exhibition Portraits transcend their historical sources–vintage photographs of anonymous African Americans, whose visages Butler transforms through vibrant layers of fabric and thread.

As the end to a most trying year draws near, hopes for a fairer and more equitable future are weighted against the injustices of the present that attempt to erode the very foundations of our democracy. Even in the wake of the U.S. election’s positive outcome, conservative politicians and right-wing extremists, cloaked in the guise of patriotism, continue to exploit symbols of freedom, including the American flag, to bolster a dangerous authoritarian nationalism and commit atrocities against American citizens, immigrants, indigenous peoples, and Earth.

Metropolis | Ken Isaacs Wanted to Retool the Way We Live by Justin Kamp • February 18, 2020 New City | Before the Tiny House: Inside the Matrix Dives Into the Design Legacy of Ken Isaacs by Michael Workman • April 14,…