For the Birds: Reimagining the Future with Jenny Kendler

August 27, 2019 / 0 Comments

Chicago is part of the Mississippi Flyway zone, one of the largest bird migration corridors in North America. It follows the Mississippi River some 2,500 miles from its most northern point in Minnesota southwards to the Gulf of Mexico. According to the Audubon Society, more than 325 bird species use the Mississippi Flyway. Growing up in the Midwest, these migratory patterns always defined the seasons: dark flocks flew south for winter; warbling swarms returned each spring. However, their ebbs and flows have now faded from my view, partially obscured by the skyline of the city, but more critically because of diminishing bird populations along the flight path of the Mississippi River.

Environmental artist and activist Jenny Kendler reminds us of the essential importance of the life and ecologies that make up the Mississippi Flyway in her empathetic works that speak urgently to the effects of climate change upon birds and humans alike. In fact, her practice and its varied forms – ranging from sculptural to sonic, from participatory to discrete actions – extends its advocacy to all species of our planet, making visible the critical issues at stake in the Anthropocene.

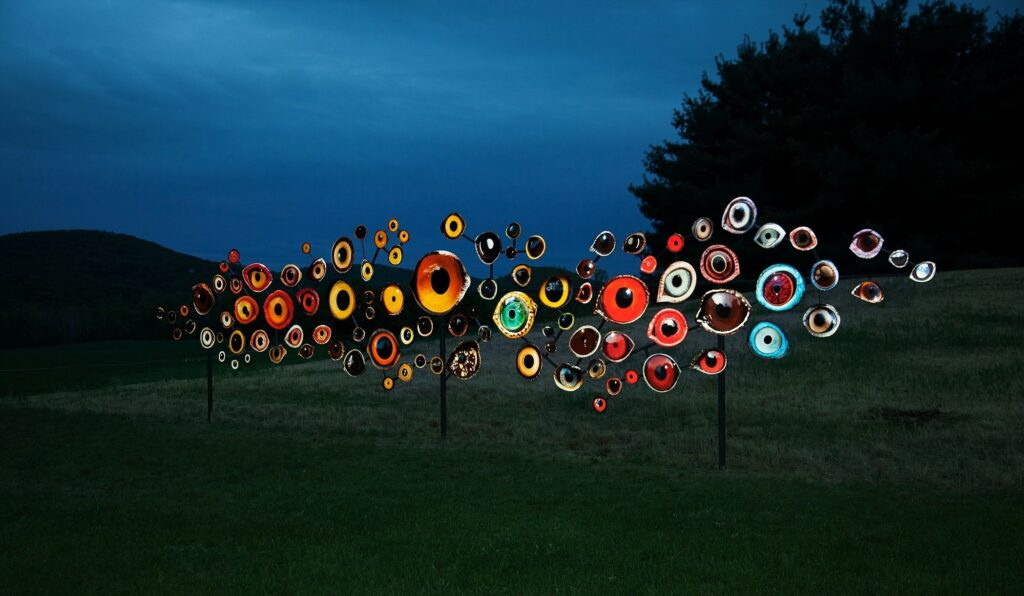

Recently I met Kendler at The 606, an adaptive-reuse trailway on Chicago’s near northwest side and the site of her temporary sculpture Birds Watching (2018). We were joined by a group of students to whom she gave each and myself a four-leaf clover, as well as a red-breasted robin who sat perched atop the work’s monumental structure – an act of “artistic engagement” according to the artist. Initially shown in the group exhibition “Indicators: Artists on Climate Change” at Storm King Art Center last fall, Birds Watching inverts the hierarchical gaze of humans upon nonhuman species by confronting viewers and passersby with the watchful stare of 100 colorful birds’ eyes. Varying in hue and scale, each eye embodies a bird species currently in danger of extinction, among them the common raven, the sage grouse, several waterbirds and owls, including the snowy owl represented here with the largest eye. Fabricated from reflective sheeting used to make road signs and mounted on a forty-foot horizontal steel frame, the eyes emit a glimmering glare that emulates the refractive glow of a bird’s eye at night. Caught in a mutual gaze renders human and avian life equal and part of a shared ecosystem, an allure that is also aesthetic in which the viewer is transfixed by the work’s vibrant pattern of ocular forms.

This reciprocal act of seeing and being seen becomes the impetus for a broader range of somatic and aesthetic experiences that extend beyond Kantian ideas about nature and the sublime. And while beauty in both content and form is integral to the efficacy of Kendler’s work, her interests ultimately lie in the viewer’s existential awakening to the impact of human activity on the environment, including their own. For Kendler, art is a form of “enchantment,” a concept not unlike artist and critic Suzi Gablik’s notion of “re-enchantment,” which imbues art with a higher moral purpose centered on social and environmental justice.

The global effects of climate change and habitat loss upon bird species across all regions of the world is the subtext for Kendler’s sonic work The Playhead of Dawn (2018-19). Living amidst the cacophony of an urban environment, we are no longer awakened by the whistles and trills of birds singing to greet the sunrise. Kendler rectifies this experiential injustice in her site-specific installation created in collaboration with sound artist Brian Kirkbride for the Arts Club of Chicago’s Garden Project series exhibited last winter and fall. Drawing on a massive database of recorded birdsongs, the four-channel sound piece played 240,000 field recordings of the planet’s 10,000 bird species that imagined the chorus of dawn as it unfolds across Earth in a single day. Each channel denoted the four regions of the world (Northernmost, Central North, Central South, Southermost), visually represented by four LED signs that scrolled the names of all the birds singing at a given moment and their locations. The signs and songs ran simultaneously over a twenty-four hour period (copying Earth’s rotation), thus one could track their aural experience in Chicago alongside, for example, that in Taiwan. While at once filling the courtyard garden and nearby cityscape with a continuous loop of avian song, the piece occasionally emitted the hum and din of human development, a major threat to bird populations.

Kendler’s ongoing interest in avian conservation and ecologies is the focus of several other works, including the performance Offering (2017), in which the artist painted her left ear red and filled it with nectar as an offering to local hummingbirds. For Kendler, creating empathy between humans and nonhumans is fundamental to our understanding of the responsibility we share in our collective survival. In her multimedia installation Tell It to the Birds (2014), the artist designed an interactive space for interspecies dialog in the form of a confessional, whereby participants entered a shelter and shared a secret with nature. The domelike structure – its black exterior fashioned from recycled tshirts ; its interior covered in a green-hued, lichen-printed fabric – suggested an inverted bird’s nest or animal shelter as well as Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic domes, a symbol of utopian (now lost?) ideals. Inside, a microphone connected to custom computer software translated each confession into one of eleven birdsongs belonging to a bird species under threat, chosen by the viewer from a printed takeaway poster that served as a field guide. Embellished porcelain figurines of the endangered birds were displayed nearby on a series of small shelves mounted to walls swathed in a lichen-printed wallpaper that camouflaged the avian statues as a form of protection.

Kendler created Tell It to the Birds in partnership with the Natural Resource Defense Council (NRDC), an environmental advocacy organization where she has been an artist in residence since 2014. NRDC has regularly partnered with artists working with climate-related issues at EXPO Chicago, the annual contemporary art fair where the work was on view, and on projects elsewhere, facilitating collaborations between artists and environmental experts. Kendler’s ongoing project Milkweed Dispersal Balloons (2014-) was also created during her residency with NRDC and in partnership with the Pulitzer Arts Foundation in St. Louis, for which the work was initially conceived. Just as several bird populations are under threat, so too is the North American monarch, in large part due to commercial weed killers that destroy milkweed, this butterfly species’s sole source of food and thus survival. Traveling across the Midwest along the same migration path of the monarch, Kendler has outfitted a food cart with clear latex balloons filled with milkweed seeds; participants take the balloons home and pop them, distributing seeds that will later grow into plants for monarchs to feed.

The generative and regenerative nature of such projects belongs to a practice that thoughtfully considers the impact and legacy of its own material forms. Thus several works are biodegradable, including a series of Venus statues crafted from soil and prairie seeds, and a library of books related to climate change “biocharred” then buried in the ground to replenish the soil with carbon. The cycles of loss and eventual renewal addressed here and throughout Kendler’s work perform an elegy that mourns what has been already lost and speaks to the realities of an uncertain future, while still calling for human action. However to address the crisis of extinction, Kendler is “against hope,” which she sees as a form of inaction, but rather for the creation of new models, in which art and artists assume an essential role. “Art is a form of enchantment, and therefore the opposite of despair,” Kendler has written. “When successful, art can extend a tenuous thread towards reconciliation, and envision worlds otherwise.” (1)

How contemporary artists, including Kendler, are responding to the ecological crisis was the subject of the recent symposium organized by Christie’s Education, New York, which explored the critical role of the arts in facilitating the dialog around climate change.(2) Revealed was a diverse array of collaborative approaches to which artists bring imaginative thinking and creative tools that help us visualize and conceptualize the challenges of the present and reimagine possible futures. Although Kendler’s works often circulate within artistic channels, whether a museum or gallery or culturally administered public site, the interdisciplinary nature of her research-based projects creates opportunities for forging new alliances around common goals for environmental remediation, at the same bringing ecological awareness to new publics. Thus balancing aesthetics and advocacy is at the core of Kendler’s environmental practice (or what artist Newton Harrison terms “counter-extinction work”), one that reminds us that human and other life forms are interdependent, coequal forces.

Notes

1. Jenny Kender, “Against Hope,” The Brooklyn Rail, June 2019, https://brooklynrail.org/2019/06/criticspage/Against-Hope. Accessed August 27, 2019.

2. The symposium The Role of Art in the Environmental Crisis took place at Christie’s Education, New York, June 11, 2019.

[…] interventions that make publics aware of the impact of human activity on Midwest bird species (Jenny Kendler) to city-scaled projects that connect citizens to local water systems and ecologies (Mary Miss). […]