To Belong: Narratives on Citizenship and Migration

May 18, 2019 / 0 Comments

Loss takes many forms. Within the last two years, I lost both my parents and a sister. Their passings were followed by much personal grief, of course, as well as an existential rethinking about the meaning of absence and belonging. What binds us to place, to each other, to the larger world? And while loss is inherent to the cycles of life that define who we are as human beings, catastrophic loss – whether by violence, poverty, social oppression, climate change, or environmental disaster – plagues our political present, rupturing the ties that connect us to home and to the earth beneath our feet. Mass movements in global migration come out of such devastation and upheaval, in 2018 displacing 68.5 million people according to the United Nations Refugee Agency (Note 1). This decade’s flow of people across physical and geopolitical borders has ignited contentious debates on the definition of citizenship and the role of government in protecting individual and collective rights.

Several recent exhibitions in Chicago broadly represented the critical, complex relationship between citizenship and immigration. Whether through material, spatial, or conceptual means, the artists, architects, and cross-disciplinary collaboratives on view imagined new forms of civil belonging to posit alternative visions of how we might inhabit the world. Together they countered mainstream narratives of mass migration and sensationalized images of the global refugee crisis by rejecting universalizing descriptions of the public citizen that exclude “plurality and difference.“ (Note 2) Instead, citizenship was presented as a diverse web of social relationships and territorial conditions through which the political subject navigates and lives.

Living Architecture

The more than 50 artists whose works comprised “Living Architecture” at 6018North explored the historical and continued role immigrants have played in the construction of Chicago’s cultural and civic identity, challenging views of immigration as a source of social conflict rather than continuity. Either immigrants themselves or first-generation Americans, these artists impart a humanistic, even corporal, view of the urban environment, whereby the city becomes a living, breathing entity built on the imagination and toil of immigrant labor, including artistic labor, rather than brick, glass and steel. This narrative reinforces the history of the exhibition’s site: a dilapidated nineteenth-century mansion in the city’s ethnically diverse Edgewater neighborhood that originally belonged to Max Eberhardt, a German immigrant and lawyer for immigrant rights. Eberhardt hired architect Arthur Woltersdorf, also a German immigrant and author of the book from which the exhibition takes its name, to design his home. Today it is 6018North, an alternative venue for experimental art directed by Tricia van Eck, who co-curated Living Architecture with Teresa Silva and Nathan Abhalter Smith. Using the building’s past and current history as its conceptual ground, 6018North became the architectural framework for this series of site-specific installations and interventions that made visible the contributions of immigrants to the creative life of the city.

Within the context of both the exhibition and the current discourse on migration, the red carpet that permanently graces the venue’s front steps became a heightened symbol of welcome, affirming 6018North’s role as a space for community and Chicago’s status as a Sanctuary City. However, Entre (Between), (2018), a vinyl banner by artist Alberto Aguilar that reads “iiiiiiin” on the exterior of the surrounding iron fence and “fluxxxxx” on its interior, places visitors in a state of purposeful uncertainty echoing the plight of the refugee.

Rights to entry and passage, how and for whom were addressed throughout the exhibition, from a mirrored archway by Tom Burtonwood and Maryam Taghavi installed just above the doorway that warps and skews one’s reflection as an illegible identity to Eugenia Cheng’s Sunset on the American Dream (2018) that greeted viewers once inside. Cheng’s wall-sized chalkboard drawing renders paths to U.S. citizenship as a giant family tree, identifying the many means to entry that have been taken or imposed, such as “visitor,” “born,” “slave,” and “immigrant,” the latter being the largest route/root. The artist’s choice of materials reinforces the history lesson the work is meant to convey – the United States has always been a nation of immigrants. But the artist’s message was tempered elsewhere in the exhibition when one encountered a fabric banner by Aram Han Sifuentes, in which the titular words “America Hasn’t Been Great Since 1492,” are emblazoned across a map of the world.

Two works by Kirsten Leenaars addressed the hopes and dreams of today’s immigrant and refugee youth. Part of the artist’s ongoing documentary project (Re)Housing the American Dream (2015-), this series of community-based programs gives youth the opportunity to voice their stories around housing and segregation. Represented within the exhibition was an offset print that states a manifesto for a fair and just future hung opposite the video New and Definitely Improved (2016). In the latter work, diverse middle-school students stand next to model dream houses they’ve constructed themselves and sell viewers on their merits and amenities. “This is a Trump-free zone,” states one young Latina. “Trump has never stepped foot in this house.”

The youth’s rather modest aspirations for basic comforts and freedoms were set in sharp relief when viewed against Roni Packer’s installation Entitled (2018) that transforms painted bubble wrap draped across a large window into a fanciful scrim of golden yellows and light. This common plastic used to protect and transport one’s belongings is used as a material metaphor for those who, as the title suggests, have the rights and resources to bring their personal possessions when entering one country from another.

Such privileging has historically been afforded to earlier waves of European immigrants, the contradictory views on which are explored in two videos by Irina Botea Bucan. In Encountering Monumentalization (2018), a Romanian emigre living in Chicago and builder of public monuments expresses his conservative political beliefs. His views clash with the progressive ideals expressed in the opposing work Phalanster (2014), in which a history teacher shares his research about the Romanian city of Scaeni, whose nineteenth-century architectural structures are based on the socialist utopian theories of French philosopher Charles Fourier.

The exhibition’s stated themes of immigrant artistic labor were more directly addressed in those works that excavate the architectural histories of Chicago. The multimedia installation of Amanda Assaley and Qais Assali deconstructs the misappropriated architectural ornamentation used in the façade of the city’s Medinah Temple; like many Shriner buildings, it is an example of Moorish Revival architecture popular at the turn of the last century that often exoticized its sources. Concrete castings of the building’s decorative reliefs appear as toppled ruins across the floor of an upstairs room, drawing the viewer’s attention to the distorted geometric patterns and linguistic symbols that misrepresent Arab culture.

Jan Tichy brings his ongoing interest in László Moholy-Nagy to two installations that pay homage to the artist’s experimental works with light and to his role as founding director of the New Bauhaus (today the Illinois Institute of Technology). Both works are installed in bathrooms: downstairs, a red neon sign spells the word “Jew,” a reference to why this Hungarian-born artist fled Europe in 1937; upstairs, a video projection illuminates the dark room in geometric fields of white light reminiscent of Moholy’s own work. Transforming these intimate spaces of personal privacy into sites of refuge, Tichy reminds us of Chicago’s legacy as place of asylum, and of the integral role immigrant artists and architects have played in defining the city’s cultural heritage.

Stateless

Whereas “Living Architecture” presented a local, site-responsive take on immigration, “Stateless: Views of Global Migration” at the Museum of Contemporary Photography highlighted personal narratives of challenge and survival from the perspective of eight international artists and photographers, some themselves political refugees. Various works adopt a quasi-journalist approach. Daniel Castro Garcia’s large-format color photographs, for instance, follow the individual experiences of sub-Saharan migrants, particularly youth, who crossed the harrowing waters of the Mediterranean seeking asylum in Europe. Beginning in 2015, the photographer traveled to various refugee camps, which he revisited over the course of several months, an embedded practice – what Alfredo Cramerotti terms “witnessing” – that goes beyond mere reportage to impart a more empathetic view of this humanitarian crisis.

Basing her documentary project on interviews, Bissane Al Charif’s multimedia installation Women Memories (2013-16) shares the accounts of ten Syrian and Palestinian-Syrian women who left war-torn Syria for safety elsewhere. In one video, unidentified images of Damascus and Beirut (where some of the women now live) become the backdrop for captioned voiceovers of their individual memories of home; in a second video, the women imagine their lives in ten years as two young girls innocently dance and spin within a private interior. A grid of related photographs installed nearby depict personal objects (watches, jewelry, keys, IDs) that the women took with them, mementos from their former lives and talismans for an uncertain future.

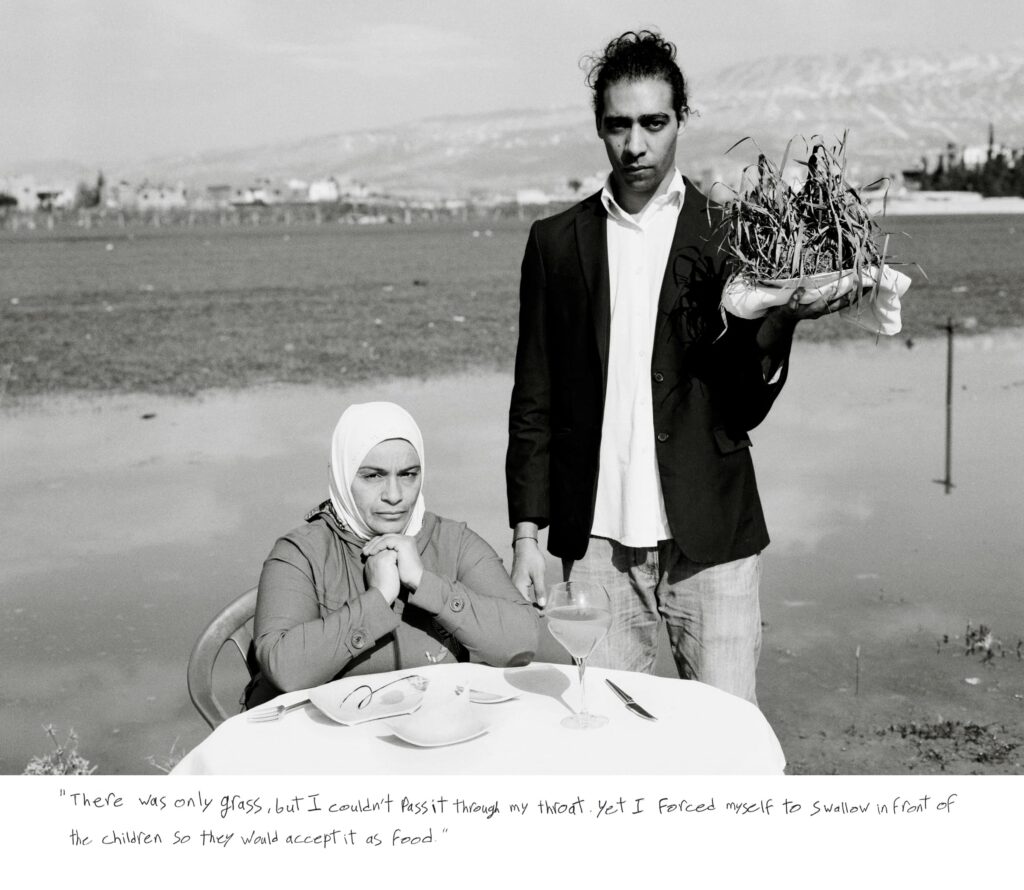

Other artists employ strategies of role playing and reenactment that recast the political traumas of their subjects as staged scenes, creating highly subjective, even surrealistic images to construct psychological portraits of migration. For his black-and-white photo series Live, Love, Refugee (2015), Omar Imam worked with displaced Syrians living in a Lebanese refugee camp to recreate their nightmares and dreams, as a means for self-expression and eventual healing. Depicted is a diverse array of protagonists, each posed with a set of props within spare settings that often use the camp’s white tents as a theatrical backdrop . A quoted passage in handwritten text appears beneath each photo and reveals their individual heart-wrenching and heart-warming stories, including a mother who ate grass to convince her children it was food and a husband who performs television shows for his wife who is blind.

An empty casino is the setting for Shimon Attie’s The Crossing (2017), a film whose actors are all Syrian refugees. Here, seven players sit lifeless around a roulette table; each places a bet then silently disappears from the scene until only one remains. Their elegant black attire hides the realities of the recent passage taken by many across the Mediterranean Sea; however, their stoic expressions and listless movements cannot mask the trauma of the experience. Attie’s slow-motion camera work and immersive installation, which also includes an audio track of water and wind, intensifies the work’s (and exhibition’s) themes of perilous journey, personal suffering, and risk.

Dimensions of Citizenship

The strength of “Stateless” was the voice it gave to individual stories of migration and to artists whose works offer alternative realities of the global refugee crisis. “Dimensions of Citizenship: Architecture and Belonging from the Body to the Cosmos” also took a macro view of displacement and belonging, asking what means to be a citizen through the lens of architecture and design. Recently on view at Wrightwood 659, “Dimensions of Citizenship” was the official U.S. entry of the 16th International Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale, a joint curatorial project of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and the University of Chicago, who served as co-commissioners. Reconfigured in Chicago for the spaces of this private venue devoted to architecture and socially engaged art, the exhibition identifies citizenship as fundamentally architectural. As the curatorial statement poses: “We define the term [citizenship] as a tangle of rights, responsibilities, and attachments linked to the built environment. How might architecture respond to, shape, and express the rhizomatic and paradoxical conditions of citizenship?”

The pluralistic dimensions of citizenship were conceived as a series of seven platforms or scales – Citizen, Civitas, Region, Nation, Globe, Network, Cosmos – that formed the exhibition’s organizing principle and to which seven transdisciplinary teams responded. The result was a diverse range of projects that proposed both on-the-ground solutions and speculative designs that right the injustices of exclusion and reformulate the conditions of belonging. The disparities between how one lives in the world and who controls access to resources are made visible in In Plain Sight (Globe), a data imaging project by Diller Scofidio + Renfro, Laura Kurgan, Robert Gerard Pietrusko with the Columbia Center for Spatial Research, shown here as a room-sized projection. Using Black Marble imagery (NASA satellite images of the earth at night), the work reveals in remarkable detail clusters of human activity: lights indicate major population centers, energy and power sources, while darkness reveals gaps in the network and areas of those living outside the grid. Such comparisons render, for example, the inequities of recovery efforts in the United States after hurricanes Harvey and Maria: Houston was without power for 11 days; Puerto Rico for 120. Not unlike Buckminster Fuller’s World Resource Inventory (1963), his influential research report that mapped the global distribution of resources, the applications for this seem endless and would hopefully become a tool for developing new infrastructure and energy sources in underserved areas of the world.

Environmental justice and remediation are explored in two projects that define citizenship as part of a larger ecosystem of shared responsibilities that transcend regional and national borders. Ecological Citizen (Region), a multimedia installation by the landscape architecture and design practice SCAPE, gathers physical objects (fascines, stacks of coir or biodegradable logs), a film and other documentary materials used in a case study of the intertidal landscape of the Venetian Lagoon, which is severely impacted by erosion. These architectural structures will later be deployed to help regenerate similarly threatened marshlands in other regions of the world. The environmental toll of Trump’s proposed Border Wall upon the Tijuana River Watershed is the subject of MEXUS: A Geography of Interdependence (Nation) by the San Diego based architectural practice Estudio Teddy Cruz + Fonna Forman. A mural of the cross-border landscape reveals an interconnected network of mountains and waterways shared by the United States and Mexico, while a video reimagines the 2,000-mile stretch as a “transborder commons” where national interests give way to mutual values based on sustainability across the region.

These acts of environmental stewardship create a portrait of global citizenship based on collaboration and common goals for ecological equity. But as literary critic and theorist Lauren Berlant reminds us, citizenship, particularly in the United States, is “…best thought of as an intricate scene where competing forces, definitions and geographies of freedom and liberty are lived concretely.” The reality of these competing, often contradictory forces have created “…uneven access to the full benefits of citizenship,” Berlant continues, in which “…the historical conditions of legal and social belonging have been manipulated to serve the concentration of economic, racial and sexual power in the society’s ruling blocs.” (Note 3).

Histories of racial exclusion that have denied Black citizens visibility in the democratic public sphere are at the foundation of two works by Chicago-based collaborations that advocate for the personal rights and freedoms of Black citizenship. Thrival Geographies (In My Mind I See a Line) (Citizen) by Amanda Williams + Andres L. Hernandez and Shani Crowe, honors the lives of Black women in American cultural and political life. This monumental structure takes its parenthetical title from a quote by Harriet Tubman, in which the line toward freedom is imagined but never reached. Made of steel and several feet of hand-braided cords, the suspended form evokes a space-aged pod or protective cocoon that viewers can enter then sit on a hanging swing. The work’s themes of containment, transformation, and mobility combined with hair and other bodily symbols imagine a spatial dimension in which Black women rise versus merely exist. (Although outside the parameters of this exhibition, Williams brings similar themes to her recently commissioned public monument of Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm, Our Destiny, Our Democracy, made in collaboration with Olalekan Jeyifous for Prospect Park, New York, as part of a new initiative to create public monuments commemorating women.)

Stone Stories (Civitas) by Jeanne Gang/Studio Gang envisions new forms of civic monuments that challenge problematic histories of enslavement. Part of a waterfront revitalization project led by Gang in Memphis, TN, Stone Stories also mines the contested legacy of the site: once a thriving, commercial port along the Mississippi River built on the cotton industry and on slave labor, now unused and neglected. During the project’s initial phases, two confederate monuments, including one of Jefferson Davis that faced the riverfront, were removed amidst public demonstrations, transforming the landing’s uncomfortable past into new opportunities for its future. To this end, cobblestones that mark this six-mile stretch of this riverfront landscape form the artifactual basis for an ongoing public project that engages local citizens to imbue the repurposed stones with their own narratives for the creation of a new public monument. For “Dimesions of Citizenship,” some 500 cobblestones traveled from Memphis to Venice for the Biennale then Chicago, where they were reinstalled as a moundlike platform from which to view various materials documenting the history of the landing and proposals for its reincarnation. Also included was a video of community members who share their personal connections to Memphis, alongside their ideas for reclaiming the waterfront as a public space of civic pride.

The memorial function of both these projects resonated within the exhibition, connecting abstract definitions of citizenship as framed by the show’s seven scales to the “everyday lives of embodied subjects.” (Note 4) And while “Dimensions of Citizenship” offered a broad platform from which to consider architecture’s role in shaping the multiplicity of modern citizenship, I question the efficacy of the larger biennale project (whether for architecture or art) in channeling the discourse on citizenship and migration into moments for real change. I write this as the battered remains of a ship that carried almost 1,000 refugees who perished crossing the Mediterranean Sea is docked at the Arsenal in Venice as part of this year’s Biennale. The vessel originally left Libya for Europe in spring 2015 only to meet a devastating fate; it is now Barca Nostra, an artwork by Christoph Büchel that appropriates and re-presents the salvaged ship as a monument to those who died. I have not experienced the work but am troubled by the reframing of this artifact of human tragedy within the context of artworld consumption, where its value as an object of spectacle seems to supersede its function as an instrument for changing the political conditions at the core of this transnational crisis. In other words: How can art transfigure despair into political action? How do viewers respectfully mourn, then advocate for agency? How do we transform loss into belonging?

Notes

Exhibition information: “Living Architecture” was on view at 6018North September 3, 2018 – March 31, 2019, and will travel in new iterations to the Lubeznik Center in Michigan City, Indiana, November 1, 2019–January 4, 2020, and to the Chicago Cultural Center in summer 2020. “Stateless: Views of Global Migration,” was on view at the Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago, January 24 – March 31, 2-19. “Dimensions of Citizenship: Architecture and Belonging from the Body to the Cosmos” premiered at the 16thInternational Architecture Biennale, and was on view at Wrightwood 659, February 28 – April 27, 2019.

- As cited by curator Natasha Egan in exhibition brochure for “Stateless: Views of Global Migration.”

- See Rosalyn Deutsche, “Agoraphobia,” in Evictions: Art and Spatial Politics (Cambridge, MA and London: MIT Press, 1996), p. 310.

- Lauren Berlant, “Citizenship,” in Keywords for American Cultural Studies, eds. Bruce Burgett and Glenn Hendler (New York and London: NY University Press, 2014), pp. 37-38.

- Ibid., p. 40.